from Poisoning Paradise: An Environmental History of Madison

By Maria C. Powell, PhD

Oscar Mayer: Another successful Chicago industrialist sees profits in Madison

Oscar Mayer and Co. was established on Madison’s northside after the Mayer family purchased the defunct Farmer’s Meat Packing Cooperative. The company was located on the edge of a large marshy area where at least one Ho-Chunk village and several mounds were located.[1]

The cooperative, established in 1915, was intended to provide a direct market for Wisconsin farmers’ livestock and compete with Chicago’s meat packing industry. But nearby factory owners, residents, and even the pro-industry Board of Commerce intensely opposed this.[i] “At that time,” Mollenhoff wrote, “packing plants were widely considered to be one of the worst possible neighbors. People especially hated the screams hogs let out when they were killed and the stench of drying hair and fertilizer.”

The mayor and an alder visited other cities with packing plants and interviewed residents nearby. When they returned, they told the council that packing plant neighbors didn’t find them objectionable, and threatened that if Madison didn’t find a location for it, the packing plant might be located in Janesville.[ii]

While opposing the eastside side location for the plant, the Board of Commerce worked to find another site, eventually recommending a site just southwest of the new Burke sewage plant, in a large wetland area near Starkweather Creek where “the noises and smells of a packing plant could hardly be offensive, since they would be far removed from the city and in an area that would never be attractive for homes.” The common council unanimously approved the site and the plant was connected to the sewage plant and city water. The city also gave the cooperative 20 acres of land, with a quid quo pro agreement that the site be annexed to the city so its tax revenue would benefit the city.[iii]

The farmers’ cooperative failed after a few years due to financial difficulties and World War I labor unrest. In 1919, Oscar G. Mayer, the Harvard educated son of Oscar F. Mayer, founder of the successful Chicago meat company Oscar F. Mayer and Bro., convinced his father to invest in it. The younger Mayer, who lived in Chicago at that time, discovered the failing cooperative on a drive while visiting his wife’s sister and her husband, president of the American Exchange Bank, who lived in Madison on Mansion Hill. It was purchased by the Oscar Mayer family for $300,000, and eventually dubbed Oscar Mayer & Co.[iv]

Branding, public relations, and science

Like Madison-Kipp, Oscar Mayer grew rapidly and also played a central role in the development of the city’s industrial northeast side. By 1920 the company was the fifth largest packing plant in the country, and many additions to the plant were constructed in the 1920s. The company also built homes nearby for its workers in the 1920s and, like Kipp, advocated and helped pay for city streetcar service to the factory.[v]

As Oscar Mayer profits boomed, it became known for its aggressive public relations, product branding, and many innovative “firsts” in the meat packing and packaging technologies. The company clearly had abundant resources to advertise regularly in Madison newspapers. In the 1920s, numerous Oscar Mayer advertisements gushing about its products appeared in both the Wisconsin State Journal and The Capital Times, as well as multi-page historical pieces about the company.

Company marketers were sophisticated—though often humorously sexist— in their advertising. In 1925, The Capital Times reported that Oscar G. Mayer encouraged “market men” at a meeting of “The Wisconsin Retail Market Men’s Association to promote the companies “ready-to-serve” meat products to “modern girls” who “have mastered shorthand, but perhaps neglected to absorb kitchen finesse.”[vi] Mr. Mayer explained that “enthusiastic but untrained housewife-bride who has just left a typewriter for a happy home of her own can go to the retail market and buy meats all ready for the table.”

Oscar Mayer and Co. also created a thriving ice business ice—and later sold “coolerators,” early versions of a refrigerator. Initially, ice was harvested from Lake Mendota, but in 1922 the company sank a deep well onsite and constructed a facility to produce ice onsite, which they sold and delivered to businesses and residents. A 1922 front page article in the State Journal bragged that their deep well produced “20,000 gallons per hour” and water “of the highest degree of purity.” Countless advertisements for the company’s “pure, sanitary” ice from deep artesian wells appeared from the 1922 through the next several decades.[vii],[2]

Not just a meat-packing company—also a scientific research and innovation center

In time, Oscar Mayer did much more than raise and slaughter animals and produce processed meat products. In addition to its branding successes, it was very proud of its scientific innovations—especially related to the mass production of “uniform” meat products, which became a key part of its brand. Newspaper promos in 1920 said the “plant stands for every modern ideal” and “embodies the highest achievements of meat packing science…”[viii] In 1924 it became the first to introduce pre-sliced bacon in stores.[ix]

The company eventually employed several research scientists. In December, 1929, the Wisconsin State Journal said the company would start its own “Research Bureau” at the plant that “will include a laboratory for experimentation in new food and medicinal products, package product research, utilization of wastes, and chemical control, including analysis of ingredients used in the processing of meats.”[x] A year later, the paper reported that Dr. D. H. Nelson from the University of Wisconsin, who specialized in chemistry and bacteriology, was hired to direct the lab.

As it grew, several laboratories were built onsite, where scientists developed new types of processed meats, pharmaceuticals for treating animals, insecticides for animal and factory pests, and spices for meat products.[3] Oscar Mayor scientists also developed—and the factory then produced onsite—first-of-a-kind plastic packaging that it used for its products and sold to other meat companies.[4]

Over time, Oscar Mayer and Co. became a mini-city in itself—with worker showers and cafeterias, an onsite coal-fired power plant, incinerator, landfills, a wastewater treatment plant, and several deep water production wells.

Oscar Mayer thrived in the 1920s

In 1922, a State Journal article “Mayer Packing Plant Ships Products to All the World,” which had no byline but appeared to be written by someone from Oscar Mayer, boasted that in the first two years in operation, the company had killed 450,000 hogs (225,000 per year), 25,000 cattle, 75,000 calves and 10,000 sheep.[xi] By the end of 1922, claims increased to 1400 hogs per day, and company officials hoped to kill 2000 hogs a day in 1923.

Many details were provided on how hogs were killed, and steps the company took to assure a sanitary process. Six federal government inspectors, on duty at the plant “at all times,” watched animal killings and “all other work connected with the dissecting of the animals, chilling process and packing.” Inspectors also insured that “all sanitary rules are enforced strictly” and the factory was cleaned with hot water every night as to keep it “in perfect sanitary condition.”

Some of the first inklings of neighborhood unrest were hinted at in this piece. “Determined to cooperate fully with the citizens of Madison in improving conditions at its plant,” it said, “the company’s staff of engineers is working on a plan whereby it is hoped to eliminate all odors complained of by residents in the neighborhood…We are willing to install the most effective system to eliminate the odors,” asserted manager Bolz.

“Efficiency,” “standards,” and “modernity” were repeated in Oscar’s promo pieces. At the end of 1925, a Capital Times article described how Oscar Mayer had incorporated Henry Ford’s “efficiency idea” and “standardized jobs” and was the “most modern” meat packing plant in the nation. As with previous articles, descriptive details were offered on the “efficient” killing operations. “The hog, after a scalding bath, which loosens the bristles, is quickly de-haired by special machinery and expert knife handlers,” it explained. “All the while the hog is moving along on trolleys. A series of shower baths and cutting operations follow, while the carcass travels continuously suspended from overhead rails. Each worker has allotted work to do and he performs it quickly, never once halting the endless processions of pork.” Adolph Bolz, manager of the plant, said, “Efficiency is the very foundation of the packing business, efficiency and volume.” The factory’s new machinery, he said “will enable us to increase our capacity to 500 hogs an hour.” [xii] A State Journal subhead the same day called Oscar Mayer “The Ford Company of the packing industry.”[xiii]

In the next few years, Oscar pieces crowed about the company’s huge markets all over the U.S. and world. “Oscar Mayer Company of Madison furnishes all parts of the United States with fresh meats” noted the Capital Times in 1926. A full page Wisconsin State Journal advertisement blared: “Every day twenty Madisons, a million men, women and children depend upon Oscar Mayer for their daily meat supply…Up and down the state, day in and day out, ply heavy trucks carrying to small towns and large cities Wisconsin’s favorite meat. Trainload after trainload leaves Madison for the great metropolitan centers in the East and Far West. Each day sees shipments leave for England and other foreign countries. The world demands Madison meat!” People want this meat because “with 45 years of experience Oscar Mayer products are handled in a perfect manner.”[xiv]

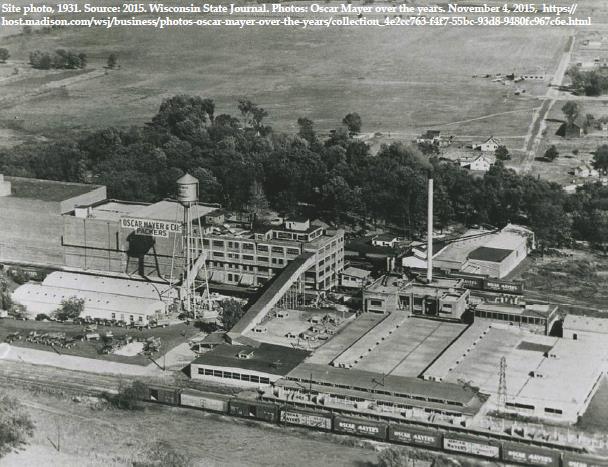

At the end of the decade, Oscar Mayer promotional newspaper articles reported big increases in profits, often including aerial photos of the growing factory, and more full-page advertisements about Oscar Mayer products going all over the world. One particularly eye-catching ad—–titled “4000 cars Oscar Mayer-made meat products were distributed to all parts of the world in 1928”—featured a hand-drawn depiction of an Oscar Mayer train zooming around the globe, and several other artistic drawings meant to symbolize what the company was about (e.g., a scientist in a lab, hogs grazing peacefully in a field, orderly carcasses hanging in the plant, a businessman at a desk, etc). It boasted of a 25% increase in volume in 1928 over the previous year. In 1929 the company released its well-known “yellow band” packaging.[xv]

Oscar Mayer worked to fend off unionization

Upton Sinclair’s powerful 1906 book The Jungle depicted horrible and dangerous working conditions, unsanitary practices, as well as poverty and hopelessness among meat-packing workers, many of whom were low-paid immigrants. Well aware of the public outrage inspired by this popular book—which also prompted the passage of new sanitation and safety laws in the meatpacking industry—Oscar Mayer took great pains to publicize in local papers how well their workers were treated, how frequently their plant was inspected, and how sanitary their factory processes, meat products and ice were.[xvi] Watching tense labor unrest beginning to develop on Madison’s eastside and elsewhere, the company also worked hard to avoid anything that might encourage its workers to unionize. It appears that these efforts were successful, at least for a while; Oscar Mayer workers weren’t unionized till the early 1930s.[xvii]

Numerous advertisement-like pieces in local papers in the company’s early years seemed purposely intended to fend off potential unionization of its workers. A large ad in 1919 in the Wisconsin State Journal stated “The workingman is awakening fully to his privileges. Everywhere salaries are rising. People are able to live better, to garnish their table more appetizingly.” It assured its workers that “we can assure conditions as happy as those in the past…no matter what crises may arise—the generous side of a square deal. We assure them rich opportunity for bettering themselves.”[xviii]

Under the headline “For Men and Women, A Good Place to Work,” another gushed about how happy Oscar Mayer workers in the “model meat-packing plant,” would say they were, if asked—and how they would praise “its cleanliness, its efficiency, its high-ideals” and “the modern spirit of kindness which permeates this plant of Oscar Mayer’s.”[xix] One bragged that “[t]his plant stands for today’s ideals in the treatment of workers” and “nowhere are workers more contented with conditions and with the opportunities for advancement, than in this plant of Oscar Mayer’s.[xx] The company also published pledges to treat its meat-producers, consumers, and citizens well in the 1920s.

Was Oscar Mayer highly efficient “community unto itself” safe for workers?

In 1928, Oscar Mayer was called a “community almost sufficient unto itself,” and a large aerial photo depicted how big it was at that point. Efficiency and sanitation were central to this “community.” Though growth in 1927 was stagnant, “profits will accrue through savings and efficiency. “Time savers, such as the automatic doors recently installed, conveniences making for more efficient work and utilization of ‘the wastes of yesterday’” would be priorities in the next year.”[xxi]

Reading between the lines, the implications for workers in this increasingly “efficient” work environment were troubling. “The local plant is as efficient, as fast, and thorough as any packing plant in the United States,” because “[c]onveyors and other labor saving devices maintain production at the maximum speed permitted.” Clearly attempting to deflect any potential concerns that this speed and efficiency might be stressful and dangerous for workers, and result in lax sanitary inspections, it added, “[a]lthough the men and equipment could handle many more carcasses than they do, United States laws forbid greater speed because of poor inspections that might follow.”

As for assuring that the factory floors and livestock yards were sanitary—work that was not very amenable to “labor saving devices,” but required human beings working at human speeds–it quipped: “Much like the job of Hercules in cleaning the giant stables, workers have these yards to clean daily. In fact, scrubbing, washing, steaming, disinfecting seems to be a pretty big item of labor all over the plant.”

Interspersed between many glowing promo articles and advertisements about the “efficiency” and safety of the factory, there were hints that working conditions weren’t exactly rosy or safe.[xxii] Inside the plant, the smell was so bad that in 1922, Oscar made plans to install a “chlorine gas ventilating system” as a “disinfectant and perfumer,” to improve the environment for workers, and especially the few women the company hired during the war (who company leaders said carried out their duties “better than men”). [xxiii],

Several reports about worker accidents involving serious injuries at Oscar Mayer appeared in local newspapers in the 1920s.[5] Among other reports, in 1925 a man was scalded in a “blast,” in 1928 a worker was hurt in an elevator crash, and in 1929 another worker was scalded. Reports of workers’ accidents and deaths continued throughout the 1900s.

In 1930, a small article was published in the Capital times: “Packing Plant Workers To Hold Meet Tonight. Opposition to the introduction of a speed up system and a reduction of hours at the Oscar Mayer Co. plant here will be discussed at a meeting of the newly organized union of packing plant employes in Labor temple tonight. It is planned to appoint a committee of the union to confer with plant officials.”[xxiv] This was the beginning of Oscar Mayer workers’ efforts to unionize. Eventually, unlike Kipp and other eastside metal workers, they were able to do so.

Oscar Mayer “community” overlords too important elsewhere to live in Madison

In the early years, neither the elder nor junior Oscar Mayer lived anywhere near their facatory; they and their families remained in Chicago and visited the Madison plant once a week. The senior Mayer, the article explained, “is so fond of Madison that he would move here if his business interests in Chicago did not require his presence in that city.” The plant’s manager, Mr. Bolz, son-in-law of the elder Mayer, “devotes his whole time to the Madison plant but keeps in daily touch with the Chicago offices.” Bolz lived in Lakewood, which is now Maple Bluff.

By 1928, Mayer family living arrangements had shifted somewhat—but clearly the company owners remained too politically busy elsewhere to live in Madison full time. A Capital Times promo “article” explained: “Mr. Mayer has his summer home in Wisconsin…and spends about five months of the year in this state. Alternating between the Chicago and the Madison plants of the concern, Mr. Mayer devotes most of his time to the home plant in Chicago…”

Apparently, Mr. Mayer had too many important political duties elsewhere to live in Madison full time. “Besides serving as vice president and general manager of Oscar Mayer and Co., meat packers, Oscar Mayer is national president of the Institute of American Meat Packers, which has a membership of about 1000 packers.”[xxv] Based on media reports, the Mayers also spent a lot of time lobbying, usually successfully, for the lowest freight rates possible to keep their meat-shipping costs down.[6]

[1] Most of these mounds were destroyed or covered with concrete as the Oscar Mayer plan expanded; one mound may still remain intake (or partially intact) but has not been surveyed to ascertain its condition.

[2] Ice production requires lots of ammonia (a nitrogen compound). This caused a myriad of surface and groundwater problems in the area for years that have largely been ignored.

[3] Oscar Mayer eventually produced and held patents on several insecticides and sold their own brand of spices.

[4] For some time, through at least the 2000s, less-than-perfect (dud) plastic packaging produced at Oscar Mayer was sent to MGE to be used as part of the fuel mix along with coal.

[5] 1925.11.5; 1926.11.1; 1928.4.28; 1928.9.29; 1929.12.10 WSJ or CT

[6] Aside from company’s operations and a strong media presence, the Oscar Mayer family didn’t seem to have the same kinds of strong public presence in Madison politics and community affairs that the right-wing, Republican Coleman family had, perhaps because they didn’t live in Madison. That said, the company, as one of the city’s largest private employers, certainly had a lot of power on city politics and decisions but used this power in different ways than the Coleman family did. When it came to environmental regulations, both companies were able to skirt around them, indicating that they had the ability to convince regulators to be lax with them or just look the other way when regulations were violated.

[i] Mollenhoff, 256.

[ii] 1939.4.16 WSJ

[iii] Mollenhoff, 256

[iv] Winterhalter, 2019

[v] 1919.8.29 WSJ, 1919.9.23 WSJ

[vi] 1925.9.14

[vii] 1922.6.22 WSJ

[viii] 1920.2.27 WSJ

[ix] Winterhalter, 2019

[x] 1929.12.31

[xi] 1922.6.22 WSJ

[xii] 1925.12.31 CT

[xiii] 1925.12.31 WSJ

[xiv][xiv] 1926.12.31 CT and WSJ

[xv] 1928.12.31, 1929.1.2. WSJ and Winterhalter

[xvi] 1922.12.31 WSJ.

[xvii] 1930.5.12, p. 201, Levitan. See more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meat_packing_industry.

[xviii] 1919.12.31 WSJ

[xix] 1920.2.9

[xx] 1920.2.27 WSJ

[xxi] 1928.1.1 CT

[xxii] 1922.11.19 WSJ

[xxiii] 1922.11.19

[xxiv] 1930.5.12 CT

[xxv] 1928.1.1 CT