from Poisoning Paradise: An Environmental History of Madison

By Maria C. Powell, PhD

Privileged Madison’s beginnings…

Shortly after the Black Hawk War, Madison was founded by wealthy, well-connected men from the eastern part of the country. Even while many Ho-Chunk still lived in the area, townships around Madison were placed on sale in Green Bay in 1835. In Mollenhoff’s words, “most of the purchases…were not the sturdy yeomen of Jefferson’s arcadian dream, but wealthy investors whose interests were strictly speculative.”[i]

Though many wealthy men purchased land in the Madison area and played important roles in its creation, probably the most critical is James Doty. Born and raised in New York State, Doty eventually became a judge in the Michigan territorial legislature. Later he was elected to a two-year term as a legislator for the Michigan territory, and during this time became a land agent for John Jacob Astor of the American Fur Company, one of the richest men in the country. With resources and support from Astor, Doty laid out downtown Green Bay, Fond du Lac, and later Madison. In 1836 he purchased several key areas on the isthmus between Third and Fourth Lakes, including the area where the capitol now stands. He quickly laid out the town’s lots and streets, borrowing the radial street design around the state capitol from Washington D.C.’s layout, and named the area Madison after revered President James Madison, who had recently died.[ii]

Doty, who had a “network of influential friends” in Washington D.C., worked hard to assure that Madison would be selected as the territorial capital and home of the university. With his Madison design laid out and mapped, Doty sold lots in the areas around the capitol “to as many influential persons as he could so that each had a financial interest in seeing the seat of government remain in Madison.”[iii] These “influential persons” included then Wisconsin Governor Dodge’s son, the chief justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and several men of “national prominence,” including John Jacob Astor himself, who purchased two dozen lots. He sent his friends in Congress letters encouraging them to buy lots in Madison so they also would have interests in the city being selected as territorial capital. One of them was New York congressman and land speculator Aaron Vanderpoel, whom he convinced to buy a section of land on the western edge of Madison where the University of Wisconsin was eventually built. Madison was chosen as the territorial capital in 1836, and shortly after this Doty created a 900-acre “Western Addition” to Madison, which platted the university along a ridge on Lake Mendota, dubbed “College Hill.”[iv]

The state government and university, often in tandem, played powerful roles in Madison’s early growth and identity. In 1848, Wisconsin was admitted as the thirtieth state and Madison was made its permanent capital. In 1849, the Wisconsin legislature approved the purchase of 157 acres of land from Vanderpoel for the University of Wisconsin, which began operating shortly after that. The newly-formed board of regents subdivided and sold some of the acres to fund the growth of the university.[1],[v]

The presence of the state capital and university established political and academic identities for Madison right from the beginning, attracting academics, professionals and politicians from eastern U.S. to settle there even while it was still a village. But working class people, including some from other countries, also began to populate Madison and helped build the city, which grew quickly.

Indeed, an 1852 article in the Wisconsin Democrat titled “Improvements in Madison” bragged about how the town, despite “extremely adverse circumstances of the times”—namely, a depressed money market at the time—was working on “improvements…with a vigor and buoyance peculiar to the highest prospects and prosperity.” Everywhere one looks in the town, the author quipped, “your vision is met by immense piles of bricks, stone, and lumber in active transition to elegant, expensive, and permanent residences, stores, and other businesses.”[2] While other towns were showing “dilapidation and decay,” and seeing “stagnation” in business, Madison was exhibiting “health and vigorous growth” and “failures among businessmen are of rare occurrence.”

Newspapers printed many romantic odes about the city intended to attract more people to the city. Not surprisingly, most focused on the lakes. Henry Longfellow penned a poem to the lakes, “To the Four Lakes of Madison,” which was the introduction to a special 1854 Wisconsin State Journal feature, “Madison Illustrated”:

Four limpid lakes,–four Naiades

Or sylvan deities are these,

In flowing robes of azure dressed;

Four lovely handmaids, that uphold

Their shining mirrors, rimmed with gold,

To the fair city in the West.

By day the coursers of the sun

Drink of these waters as they run

Their swift diurnal round on high;

By night the constellations glow

Far down the hollow deeps below,

And glimmer in another sky.

Fair lakes, serene and full of light,

Fair town, arrayed in robes of white,

How visionary ye appear!

All like a floating landscape seems

In cloud-land or the land of dreams,

Bathed in a golden atmosphere!

The 1854 “Madison Illustrated” issue concluded that Madison had “the most delightful surrounding and climates to be found in the Mississippi basin—if not the world.” A section on the lakes, “The Four Lakes, A Scene of Loveliness,” noted that without the “embrace” of the four lakes, “Wisconsin’s capital city would be an unframed picture, a soulless body…” Lake Monona, “upon whose verdant banks a queenly city has royally enthroned herself” was described in almost magical terms: “By sun-rise and moon-rue, in day time and night time, in calm and in storm, the fairy that floats in evanescent clouds above Monona’s waters is over true to her principles of mystic grace and beauty.”

Early Madison leaders ignored the Ho-Chunk names for the lakes, at first calling them “First, Second, Third and Fourth” Lakes. But clearly aiming for more attractive names, the Madison Illustrated issue dubbed Lake Monona “Fairy Lake,” Lake Mendota “Spirit Lake,” Kegonsa “Fish Lake,” and Waubesa “Swan lake.” According to Mollenhoff, a “student of tribal lore” named Frank Hudson suggested the current names– Mendota, which he said meant “great,” and Monona, meaning “beautiful.” Lyman Draper, the secretary of the State Historical Society, suggested Waubesa (“swan”) and Kegonsa (“fish”). These names were selected, Mollenhoff suggested, because they were “syllables and euphonious.” They were approved by the legislature in 1855.[vi],[3]

What kind of city should Madison be? Elites envision “Athens of the West” resort

Madison was incorporated as a city in 1856, and by 1860 its population was estimated to be 20,000 people.[vii] In the next several decades, and into the early 1900s, deep tensions persisted among Madison leaders and citizens on whether the city should be a resort and university town, a home for factories and manufacturing, or both. In early decades of the city, sentiments leaned towards the former two. “Madison’s relatively rapid success as a northern resort during the period from 1866-1879,” Mollenhoff explained, “occurred just in time to make tourism the major alternative to manufacturing as a means of increasing city population and getting the local economy moving again.”[viii] While a minority of city residents felt that factories were essential to the city’s population and economic growth, “most Madisonians” agreed with D.K. Tenney, an early city leader, who advised the city to bank on its public educational institutions and unique natural beauty. “Madison and surroundings are the handsomest on the face of God’s green earth…No other place in the West possesses it,” Tenney pronounced.

In 1857, “Madison, the Capital of Wisconsin, its Growth, Progress, Condition, Wants and Capabilities,” by Lyman Draper and prepared by the order of the Common Council of Madison, proposed that “Madison largely already has, and must continue to attach to itself as a residence,” to certain types of settlers. The following four types of “men” topped the list: “men of refinement and education,” “men of wealth for the investment of capital,” “men with families who seek to secure for their children the advantages of Education of every grade from lowest to highest” and “professional men and politicians.”[4]

Further, Madison would be a place for healthy, vigorous people and its lakes would be central to that. Madison’s lakes, it noted, give it “the best facilities for sailing, fishing-and bathing and “render it an attractive resort for the lovers of healthy and invigorating amusement.” The lakes “must make it eventually the great Watering Place of the West” where “water may be easily raised from the lakes for water works and fountains…”

By 1877 many accepted as a “settled fact” that Madison’s “natural advantages would make it one of the most attractive summer resorts in the country” with “[n]o soot-belching chimneys, no noisy factories, and no grimy workers,” according to Mollenhoff. Instead, Madison would be a “nationally famous northern resort” and “a center of culture, learning and legislation, a city of fine homes, and the commercial emporium for Dane County.” Opposition to Madison as an industrial city was very strong among university professors, state employees, doctors, and lawyers who “constituted the backbone of Madison’s rather intellectual, professional, and salaried society.”[ix]

Though editors of Madison’s newspapers were largely pro-factory, and news coverage reflected this, strong anti-factory sentiments showed up in letters to the editor and magazine pieces. An 1889 Harper’s Weekly piece bemoaned the fact that “Madison is at intervals seized with the wish to become a great manufacturing center,” which the author felt was a big mistake. Any town with “railroads and pluck and enterprise,” he argued, can become a manufacturing town, but “few towns, however, can become beautiful and learned, or can achieve social distinction…” Madison had a bleak future if it chose the industrial route, he opined: “Madison can of course darken her skies with the smoke of countless furnaces, and cover her vacant lots with long rows of tenement houses, if she so will its…It would be a great pity if she did so, however, for the industrial West can ill afford to sacrifice those shining qualities that have made Madison famous for the paltry sake of a larger census return and the sale of a few acres of vacant land. Madison ought to be content as well as proud of her present… She is rich and prosperous and cultured; let her exist for the sake of being beautiful.”[x]

University and professional elites wanted the city instead to be a “great educational center,” and assumed as the university kept growing that Madison could prosper without many industries. Academics argued that they valued antimaterialism, intellectual achievement, and natural beauty as ideals for the city’s identity, and argued that Madison’s university-centered culture reflected these values.[xi] A faculty wife who moved to Madison in 1896 observed that “Nowhere have I seen less respect shown for the Almighty Dollar as in Madison.” UW President C.K. Adams went so far as to say that “material interests” were “sacrificed so the city could become a place of culture.”[xii] With these ideals in mind, some academic and professional leaders even began referring to Madison as “Athens of the West,” while others hoped it would become “the Oxford of America.”[xiii]

The anti-factory contingent also did not believe Madison could be a factory town and beautiful at the same time. In the words of one observer, Madisonians “loved the town and did not want it spoiled for the sake of Big Business.”[xiv] Factory opponents asked, “Do we really want to encourage factories to come here knowing that their smoking chimneys will make our skies leaden and our lakes a depository for their wastes? Is a smoky, dirty, ugly city worth the extra money such factories would bring in?”

This perspective was partly a reflection of privilege of the anti-industrialist group, who benefited greatly from the work and political connections of the wealthy easterners who founded the government institutions and university in Madison decades earlier. Further, since that time, Wisconsin’s legislature continued to generously fund the university. As Mollenhoff notes, “the anti-industry group also had the advantage of doing almost nothing to make the university and state government grow. Both were then expanding relatively rapidly and were being well-funded by the legislature.”[xv]

At times, elitism, as well as thinly veiled racism and fear, exuded from public writings of some in the anti-factory group. Some refused to buy stock in a company that wanted to locate its factory in Madison because they did not want to see “the air fill up with smoke and the streets with grimy men.” Others argued that if factories were to be in Madison, they would be separate from residences—e.g., a 1899 pamphlet, Madison Wisconsin and Its Points of Interest said that unlike many western cities, Madison “is not a dreary waste of sandy dusty streets nor smoke begrimed houses; on the contrary the manufactories and the residence portion are widely separated.”[xvi] Mollenhoff wrote that groups opposing factories in Madison did so “because they meant a great influx of “grimy workers,” many of whom would be “ignorant, poverty-crushed foreigners” that would “lower the city’s intellectual and moral standards” and “the city’s intellectual life might decline.”[xvii]

Shrewd factory owners see labor-force advantages in Madison…

Madison’s anti-factory sentiment was very unusual compared to other places in the U.S. at that time, according to Mollenhoff: “Against a backdrop of American history, Madison’s relatively large and effective antifactory and antigrowth sentiment was downright rare. Indeed, throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the rest of the country was marching to the brassy trumpets of industrialization, this articulate group of Madison opinion leaders was listening to the stringed sounds of beauty, scholarship, and culture and for the most part delighting in being out of step with the rest of the nation on this matter,” he wrote. Though Madison did eventually welcome some industrial growth, it was less than many comparable cities in the U.S.; Mollenhoff concludes that “in the absence of these values, Madison would surely have become a conventional factory town as did many other state capitals well served by a railway network.”

Despite the strong and public anti-factory sentiment in Madison in the late 1800s, some shrewd factory owners came to see Madison as an attractive place to locate their businesses. It was in the middle of a rich agricultural region, with growing numbers of farms; tools and machinery would be needed to reap bounty from the areas fertile soils for the ever-expanding agricultural markets in a growing country. Madison’s railroad system was good and growing. Also, the city’s small size, formerly seen as a negative, was increasingly viewed as an asset. In larger cities with bigger labor forces, industrial unions were becoming more powerful and labor strife growing—and smart businessmen looking to start industrial ventures knew this, knowing it meant “lower production costs” and “steadier output.”[xviii]

In this context, in 1880 John A. Johnson, an enterprising Norwegian immigrant, co-founded an agricultural implement company, the Fuller and Johnson Manufacturing Company on the east side of Madison near East Washington Avenue. In 1889 he started Gisholt Machine Company, which produced machine tools; shortly after that the Northern Electrical Manufacturing Company was founded by the inventor Conrad M. Conradson, who was recruited by Johnson to come to Madison. These companies became known as “the big three” and set the stage for what became known as the “East Side manufacturing district,” around E. Washington and Dickenson (and eventually a wider area including where Madison Kipp eventually located).[xix] None of the workers in these factories were unionized.[5]

Wake Up, Madison! The Forty Thousand Club comes to the rescue

Growth in Madison in the late 1800s wasn’t enough for pro-industrialists. At the turn of the century, Madison business leaders were extremely dissatisfied with the amount of city growth, especially given that several other Wisconsin cities had surpassed Madison in population. They wanted a bigger city, more railroads, more streetcars, more businesses, and more factories. They wanted “a metropolitan future” with “truly metropolitan walls of buildings” surrounding Capitol Square, “metropolitan” electric lights, “plumes of black smoke from factories” and “countless locomotives.”[xx]

In 1899, an editorial by Wisconsin State Journal’s editor Amos Wilder screamed “Wake Up, Madison, Wake Up,” scolding the city for being too “slow” and “conservative” and not doing enough to attract industry and capital.[xxi] He argued that the city needed an “advancement association” or “commercial club,” such as those that spurred growth and development in other Wisconsin cities like Milwaukee, and around the country. Wilder and other businessmen formed the Carnival Association, led by J.W. Groves, a piano merchant, and in 1900 this association organized “a glittering array of events and entertainment” to show that Madison was “a bustling business and commercial city with a great future.” The event was attended by 75,000 people, and spurred a series of meetings by businessmen, led by Dr. Clarke Gapen, a local surgeon, about forming a permanent organization. Dr. Gapen and these businessmen decided that to be a “first class city,” Madison needed to have 40,000 “prosperous and progressive people” by 1910—and hence the organization was dubbed the Forty Thousand Club. J.W. Groves was named president of the new organization.[xxii]

Among other things, Forty Thousand Club members began taking actions to encourage business and industry growth in Madison—such as offering incentives to business owners and industries to locate in the city, forming committees to help negotiate better railroad freight rates, endorsing stock offerings of new enterprises, and giving carriage tours of the city to prospective factory owners. Just over a year after the organization was formed, its Republican president, Mr. Groves, was elected mayor—defeating a university professor who was opposed to the goals of the club. In the years after that, the Club helped negotiate free sites and large stock purchases, the “standard demand of mobile, mercenary corporations,” for several companies, including Kipp (then called Mason-Kipp), which received a free site in 1902.

By 1910, the Forty Thousand Club had failed to reach its goal—Madison’s population was just 25,531. Regardless, the club had succeeded in convincing many city civic and business leaders that an “advancement” or “commercial club” was essential for Madison. The organization was renamed the Commercial Club. The Commercial Club eventually disbanded, but not long after this another business promotion organization, the Board of Commerce, was formed, to make Madison “a better, bigger and busier community.”[xxiii]

Madison’s progressive citizens want more services, which requires more tax money…

Madison’s progressive citizens, meanwhile, wanted “efficient, honest, and much more powerful local government, devoid of partisan silliness; a city that preserved the natural beauty of its unique world-class site; a city whose lakes were clean, not green and stinking; a city devoid of slums and poverty; a city that boasted clean milk, clean food, a sewage plant that worked, free garbage collection, and modern hospitals; a city where every citizen had a say.”[xxiv] Madison’s leaders realized that the city “could not afford to break into the metropolitan ranks” and provide the improvements citizens demanded without more tax revenue–and that factories could provide some of this money.[xxv] In 1912, the state legislature passed the nation’s first state income tax giving 70 percent of its yield back to municipalities, which made factories even more enticing to Madison’s leaders.[xxvi]

During this time, both the Wisconsin State Journal and the Madison Democrat ran passionate pro-factory stories and editorials. The editor of the State Journal, Richard Lloyd Jones, an outspoken factory advocate, wrote long editorials scolding Madisonians for their fear of factories. Mollenhoff quotes from one of Jones’ editorial series, urging citizens to “wage war on those who were ‘contented with Madison the Peaceful’…Who said we want more peace and quiet?…Let people who want to go to bed at 8:30 go somewhere else.”[xxvii]

In 1912, Jones organized a slogan contest for the city. Entries for the contest revealed the widely ranging visions for the city, some highlighting progressivism, intellectualism, and natural beauty, others focusing on money and mansions, and a few combining both—e.g.: “Madison, Healthy, Wealthy, Wise, and Witty,” “Madison, Pretty, Proud, and Progressive,” “Brains, Business, and Beauty Make Madison Move,” “Madison, Wisconsin, the Home of Progressivism,” “Madison Maintains Many Magnificent Mansions,” Make Your Millions in Madison,” and “Madison Men Make Money.”

With the tax benefits of factories becoming more necessary for city infrastructure, and cheerleading from newspapers and commercial clubs, city leaders and elected officials in time became more welcoming to factories. When Carl Johnson of Gisholt asked the city to vacate a residential block on the east side in 1906 to expand his factory, citizens were opposed and the city said no. But in 1910, Johnson enlisted the support of the Commercial Club, the business community, and even the governor, and eventually received support of the common council, “an event that signaled the beginning of an era when the common council became a friend of industrial growth.”[6],[xxviii]

The Madison Compromise

Debates between anti-factory professionals and pro-factory industrialists continued to simmer in the early years of the century. Eventually, as Mollenhoff describes, “both sides recognized that the pure version of their dream was politically out of the question since each side had enough power to thwart the other” and “could made certain concessions, win great gains, and save face.”[xxix]

Savvy industrialists realized it would be a mistake to push “the ruder kinds of factories” such as steel mills, instead promoting “high grade” factories which would employ “highly skilled, highly paid artisans who owned their own homes and sent their children to the university.” Swayed by this rationale, in 1914-1915, the Board of Commerce rejected many factories considered not “high-grade” enough for the city. By this time, however, Kipp and several other heavy industries—not exactly “high grade” or employing “highly skilled, highly paid artisans”—were already established on the city’s east side.

This argument apparently calmed the fears of the anti-factory elites that Madison would become filled with “dirty, grimy” workers, and they gradually accepted that Madison would need “people with the dinner bucket” to operate its factories.[xxx] One anti-factory representative, who had reluctantly come to accept factories in the city, condescendingly argued that it was “no more [than] common justice to desire to give to as many [laboring men] as possible the advantages…a city like Madison has to offer.”[xxxi]

However, though they had finally accepted having more factories, elites did not want these factories near their homes, nor did they want factories workers living near them. Hence, the east side was dubbed the “factory district” and the west side, where most Madison elites and professionals lived, the “residence district.” John C. Fehlandt, an attorney who lived on Langdon Street (the mansion district on Capitol Hill), proposed that Madison’s topography made the city perfect for factories and homes to coexist, because Capitol Hill nicely separated these two districts. Of course, he also certainly knew that most factory workers, unable to afford automobiles, would need to live near their work—on the east side.[xxxii],[7]

The anti-factory and pro-factory groups’ “tacit agreement”—to accept more factories (only “high grade”) and designate the East Side as the “factory district” and the West Side the “residence district”—became known as “the Madison compromise.” As Mollenhoff opines, “It was a comfortable world of cozy compartments separated by a socioeconomic fault line that even today sends tremors through discussions of municipal problems.” By 1910, he wrote, the Madison compromise “had been accepted by most opinion leaders.”

Madison, the “Model City”? Madison felt it was already perfect

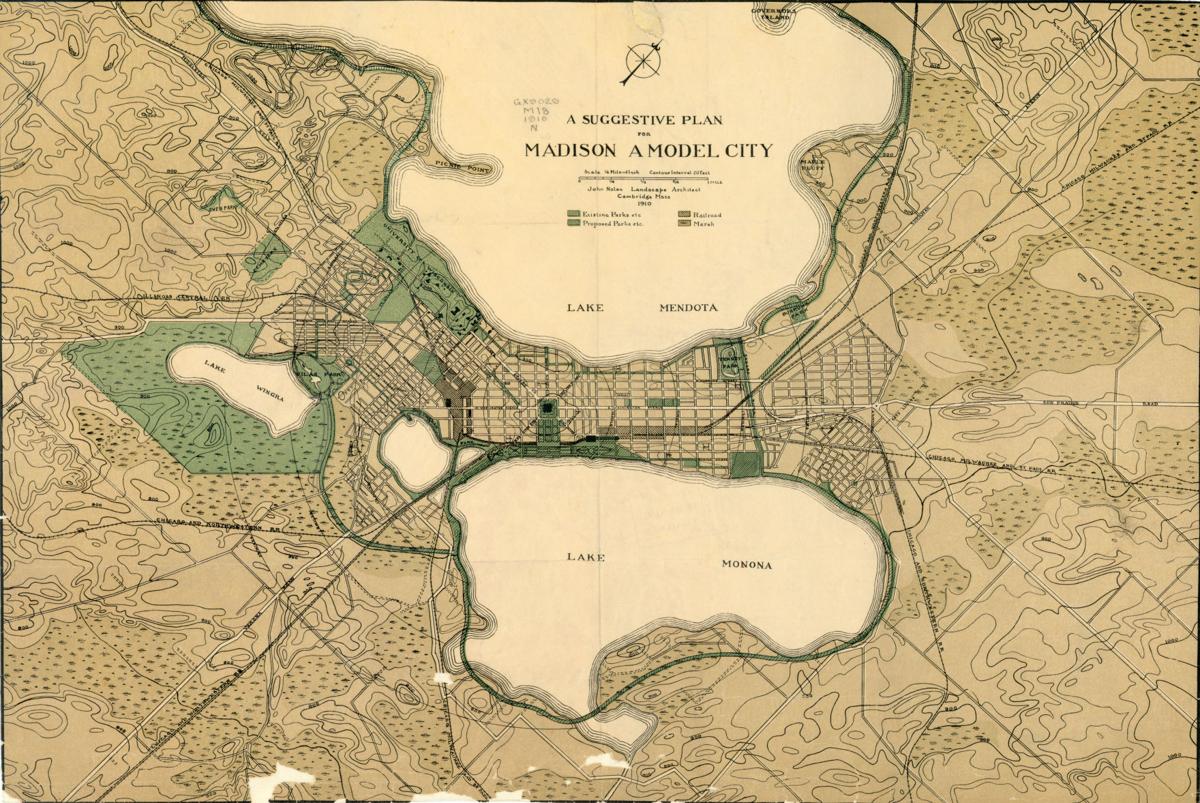

In 1908, civic leader John Olin convinced Madison officials to hire the prestigious, nationally-renowned East Coast city planner John Nolen, luring him to the city with an extremely generous pay package. According to Mollenhoff, after touring the city Nolen outlined its distinguishing characteristics, including its “incomparable site” (“a site for a city that no city on the continent could surpass”)[xxxiii] impressive public spirit, role as the capital, and the university. Because many Germans lived in the city, he expected residents would support high standards of urban design such as those in German cities Nolen admired; he also expected Madisonians to “manifest much higher concern for ‘learning, culture, art and nature.’” Echoing the Madison Compromise debates, he “did not want manufacturing to become a major justification for the city, but rather a leit-motif.”[xxxiv]

In September 1910, Nolen’s plan, “Madison: A Model City” was released to the public, and it was published in 1911. Nolen believed Madison could become a “world-class” city and “the hope of democracy.” His plan was “audacious, far-sighted, and perspicacious” according to Mollenhoff. Recommendations included a “Great Esplanade” between the capitol and Lake Monona, burying electric utilities (power poles and lines), upgrading and beautifying city entrances, tree planting, greatly expanding the university campus and arboretum and other recommendations on housing, parks, utilities, roads, and more.

Nolen also outlined deep problems in the city’s “haphazard” design—some that he believed could be addressed through future comprehensive planning. He trashed Doty’s original 1836 plans, and strongly criticized the railroads criss-crossing the city, which he felt had been “the most serious factor in Madison’s unmaking.” He recommended elimination of residential congestion, children’s playgrounds in all neighborhoods and more parks and public lake frontage. Perhaps most notably, unlike most planners of this era, his plan advocated for low-income housing.

He also urged Madison to consider the “common welfare” by adopting European design and management values such as including spacious green plazas, statues, museums, parks and playgrounds. He argued that “Madison could easily afford these amenities because it boasted considerable private wealth,” but that instead, problematically, Madison had chosen “community poverty.” To have European amenities, “Madison would have to subordinate private to public good, quantity to quality, property rights to people rights, short-term to long-term economies, and laissez-faire to planning.”[xxxv],[8]

Despite the huge amount of money Madison had paid Nolen to develop the plan, it was “virtually ignored” according to Mollenhoff, who reviewed Nolen’s plan and speeches before and after it was released. In part, Madisonians rejected Nolen’s recommendations because he seemed to be telling them that they were “tight-fisted, short-sighted, and wrong-headed” and “present and past policies doomed Madison to ugliness, mediocrity, and waste.” Madisonians preferred to think of the city as “sophisticated, cerebral, beautiful, and progressive.”[xxxvi] Further, he opined, Madison business leaders did not like Nolen’s plan because it required adoption of “major new governmental powers”—such as land use controls, zoning, subdivision regulations, etc.– which they viewed as “major assaults on their rights of private property” and would allow the state to play a bigger role in Madison’s governance. Not many Madison residents, Mollenhoff wrote, supported “such a radical concentration of local government power.” Also, Nolen’s plans would also be very expensive to carry out.[xxxvii]

While most of the key components of Nolen’s “Model City” plan were rejected, some of its key elements came to fruition over time.[xxxviii] As for the Madison Compromise, by the end of the decade—during which the city and its industries grew tremendously—it was clear that many Madison leaders and newspapers no longer viewed it as a compromise at all—that the city could have it all, as this 1919 Wisconsin State Journal column reflects: “Madison is growing rapidly, even in these uncertain times. It seems destined to grow tremendously. It has everything to commend it—educational advantages, steam railway transportation, banking facilities, nature’s bounties, and a hustling and intelligent people.”[xxxix]

Mollenhoff marked 1920 as “the close of Madison’s formative years, a period when the modern contours of the city were shaped” and “the long-simmering debate over the city’s destiny had been settled.” “Madison would be a government town and a university town and an industrial town, but not a northern resort,” he opined; its citizens had abandoned a “laissez-faire” local government approach for an “intervene-and-regulate progressive model.”[xl]

The city’s “personality,” he continued, was “well-established” by this point, and at its core were “an intense awareness of the city’s extraordinary natural beauty and the distinction of being both the capital of a great commonwealth and the home of its major university.” He called Madison leaders “button-bursting proud of these distinctions” and gushed about the vim and vigor of Madison citizens, who would forego “their pleasures and duties,” generously contributing their time, talent and money” to work for the city’s benefit and “almost against their will.”

In 1939, the eastside-westside “two Madisons” created by the Madison Compromise were deeply established and accepted; a centennial edition of the Wisconsin State Journal, quoting from city planner Ladislas Segoe’s report, wrote that “a geographic separation of its economic and social classes,” between the industrial east and professional west sides we “so pronounced that ‘socially and ‘economically, the city might be treated as two separate cities.” Academia and industry were no longer viewed as opposing enterprises; the article gushed about connections between university research and industry growth in the city.[xli]

As of 2003, the year of the edition I relied on for much of this history, Mollenhoff was confident that the city’s “core personality” remained the same, writing: “This city personality is not a musty artifact, an illusion based on distance, or a philosophical abstract. It is alive and well. It is all around us. It is in today’s newspapers and radio and television broadcasts. It is in our thoughts as we contemplate tomorrow. We contemporary Madisonians have inherited this city’s personality, and in this respect the past is part of our future. Indeed, it is this tension between our declining past and our created future that makes Madison such a beautiful, exciting, and very demanding place to live. May it never lose these qualities!”[xlii]

[1] A bill passed by the legislature in 1837-38 said the territorial university should be “located in the vicinity of Madison.”

[2] Sadly, many Indian mounds were destroyed during this phase of Madison’s development.

[3] In 1857, a document titled “Madison, the Capital of Wisconsin, its Growth, Progress, Condition, Wants and Capabilities,” compiled by Lyman Draper of the Wisconsin Historical Society, smugly noted that “…speaking of the Indian, nothing is more noticeable, as exemplifying the good taste of those who give character to Wisconsin’s Capital than the nomenclature of lake and stream and grove in all the region round about; no new Geneva spreads its crystal disc in Lake Mendota; no new Constance glimmers through the trees from Lake Monona; but Mendota, Monona, Waubesa, Kegonsa, Yahara, Peshugo, and Wingra…”

[4] It isn’t clear that my great-great grandparents, who arrived in Madison in 1851, would have fit into any of these categories, but sparse available evidence suggests not. They weren’t wealthy, highly educated, professionals and/or politicians. According to my great granduncle’s 1921 piece in the Wisconsin State Journal, he and his brothers worked as printer’s devils for the newspapers or for one of the railroads. My great grandfather, one of his other brothers, worked primarily as a caterer.

[5] The “big three” companies, Madison-Kipp, and several other companies fought hard against unionizing efforts during World War I, when several of them manufactured war-related machinery and munitions with contracts from the U.S. government. Some of them later allowed workers to unionize, but Kipp has successfully fought unionization of its workers to this day.

[6] To thank the city, Johnson rented a plush railroad car on which he took the Commercial Club leaders, the Mayor, the alders and editors of both papers to Chicago. On the trip, he gave a presentation “on the importance of city-business cooperation on industrial growth.” A formal council meeting was conducted on the train, since a quorum was present. In Chicago, Johnson treated his guests to cocktails, and hors d’oeuvres at the Chicago Athletic Club.

[7] The divide isn’t really this clean; there were already several established elite homes and prestigious neighborhoods on the east side by this time, including one just south of Kipp along the edge of Lake Monona near Hudson Park, and another further to the west on the lake. Still, as described in subsequent chapters, factory workers eventually settled in the neighborhoods immediately around Kipp, Oscar Mayer, and other north and eastside industrial areas.

[8] According to Mollenhoff, Nolen himself later characterized his 1910 city plan as “elementary and amateurish” and as “largely propaganda and publicity” but Mollenhoff noted that “For its time, Nolen’s plan was at the cutting edge.” (pg. 330).

[i] Mollenhoff, p. 20

[ii] Mollenhoff, p. 25

[iii] Mollenhoff, p. 26

[iv] Mollenhoff, p. 27

[v] Mollenhoff, p. 56

[vi] Mollenhoff, p. 46

[vii] Mollenhoff, p. 59

[viii] Mollenhoff, p. 129

[ix] Mollenhoff, p. 252

[x] pg. 433, footnote—William Willard Howard, Harper’s Weekly 33, no 1684, March 30, 1889, p. 234

[xi] Mollenhoff., 252

[xii] MD March 19, 1897

[xiii] Mollenhoff, 185.

[xiv] Mollenhoff, p. 185

[xv] Mollenhoff, p. 254

[xvi] Mollenhoff, p. 433 Footnote 61: William Willard Howard, Harper’s Weekly 33, no 1684, March 30 1889, p. 243:

[xvii] Mollenhoff cite, pg. 252

[xviii] Mollenhoff, p. 250

[xix] From the sign along the bike path

[xx] Mollenhoff, p. 239

[xxi] Mollenhoff, p. 240

[xxii] Mollenhoff, 240

[xxiii] Mollenhoff, 248

[xxiv] Mollenhoff 239

[xxv] Mollenhoff, 250

[xxvi] Mollenhoff, 250

[xxvii] Mollenhoff, 251

[xxviii] Mollenhoff, p. 251-252

[xxix] Mollenhoff, p. 254

[xxx] Mollenhoff, p. 255.

[xxxi] Mollenhoff, 255

[xxxii] Mollenhoff, 255

[xxxiii] 1921.5.8 WSJ

[xxxiv] Mollenhoff, 327

[xxxv] Mollenhoff, 330

[xxxvi] Mollenhoff, 332

[xxxvii] Mollenhoff, 334

[xxxviii] Mollenoff, p. 334

[xxxix] October 1, 1919, Wisconsin State Journal Op-Ed.

[xl] Mollenhoff., p. 404

[xli] 1939.9.2 WSJ

[xlii] Mollenhoff, p. 406