from Poisoning Paradise: An Environmental History of Madison

By Maria C. Powell, PhD

Creation of EPA in 1970

During the 1960s, inspired in part by Rachel Carson’s seminal 1962 book “Silent Spring,” the public began to demand that more be done about toxic chemicals. In 1969, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was passed by Congress with bi-partisan support, and in 1970 Richard Nixon signed it, under huge public and political pressure.

Nixon proclaimed the 1970s “the environmental decade”[i] The first Earth Day, supported by progressive Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, who was state governor from 1959 to 1963, was held on April 22, 1970 in Madison and cities across the U.S. In the years immediately following NEPA’s passage, the Democratic Party controlled Congress and there was bipartisan support for environmental protection—a political context that encouraged the rapid passage of extensive federal environmental regulations that in other time periods would likely never pass.

Several new and ramped-up federal water quality regulations were created, including the 1972 Water Pollution Control Act, which directed the EPA to set up a broad program to eliminate water pollution. Among the “interim goals” of the Clean Water Act were to have “fishable and swimmable” waters by 1983 and to eliminate all discharges of pollutants to navigable waters by 1985.

City of Madison General Ordinances (MGOs) on water pollution control

Following from these laws, the City of Madison also developed local water quality regulations in the early 1970s. Madison General Ordinance 7.47, which included permit requirements and effluent limits, was approved by Common Council and Mayor Dyke on January 12, 1972. …[ii] It stated that “no person, corporation or partnership shall discharge any non-storm water or connect any non-storm water facility to the storm sewer system, or directly into any lake or stream in or under the jurisdiction of the city of Madison, or into any ditch or drainage-way leading into such lakes and streams without first having obtained a permit as required by this Section.”

Permits would be issued by the City Engineering Department and the Madison Public Health Department “shall determine that the waste water meet applicable City, County, State and Federal water and/or effluent quality requirements and that the effluent will not pollute surface or ground waters and that the effluent will not degrade the quality of the receiving water below standards established by the State of Wisconsin.” The Madison Department of Public Health would prescribe effluent quality requirements for each proposed on-storm water discharge, subject to periodic review by the Madison Rivers and Lakes Commission. Effluent quality requirements “may be revised from time to time” and “permit holders must at all times meet revised effluent quality requirements…”

The purpose of the ordinance, updated in 1975, was “to prevent polluting or spilled material from reaching lakes or streams where it can create a hazard to health, a nuisance or produce ecological damage and to assess responsibility and costs of clean up to the responsible party.” “It shall be unlawful for any person, firm or corporation to release, discharge, or permit the escape of domestic sewage, industrial wastes or any potential polluting substances into the waters of Lakes Mendota, Monona, Wingra or any part of Lake Waubesa adjacent to the boundaries of the City of Madison, or into any stream within the jurisdiction of the City of Madison, or into any street, sewer, ditch or drainage way leading into any lake or stream, or to permit the same to be so discharged to the ground surface” (emphasis added).

Potentially polluting substances included, but were “not limited to” fuel oil, gasoline, solvents, industrial liquids or fluids, milk, grease trap and septic tank wastes, sewage sludge, sanitary sewer wastes, storm sewer catch-basin wastes, oil or petroleum wastes. Responsible parties who discharged such spill material, the ordinance said, “shall immediately clean up any such spilled material to prevent it becoming a hazard to health or safety or directly or indirectly causing the pollution to the lakes and streams under the jurisdiction of the City of Madison.”

Spills were to be immediately reported to the Madison Police Department, which would direct reports to the proper agency, and the responsible party (or parties) would be held financially responsible for the cost of cleanup. Enforcement was up to the Director of Public Health (or his/her designee) and the penalty could be up to $500 a day for failure to comply, with each day of violation a separate offense.[1],[iii]

Oscar Mayer applies for an Army Corps permit to discharge to city storm drains

About six months after MGO 7.47 was approved, Oscar Mayer applied for a permit “to deposit or discharge materials” into the Madison storm sewer system—but not a permit from the city. The request was to the Department of the Army for a permit under Section 13 of the River and Harbor Act of March 3, 1899 (The Refuse Act) (33 U.S.C. 407). The company also applied to the DNR “for certification to the effect that there is reasonable assurance this activity will be conducted in a manner which will not violate applicable water quality standards.”[iv]

City officials were concerned that this permit might interfere with its ability to regulate the company’s discharges under its newly minted Madison General Ordinances. On July 31, 1972, the city engineer wrote a memo to Mayor Dyke about the Oscar Mayer permit application.[v] He concluded that the discharge wouldn’t impact “anchorage or navigation,” that dangers to fish and wildlife were unknown, and that other water quality parameters, specifically coliform and phosphorus, should be further investigated.

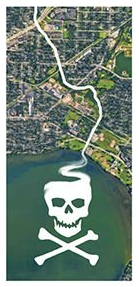

A couple weeks later, Mayor Dyke wrote to the Department of the Army with questions about the permit.[vi] He explained that Oscar Mayer’s discharges would go to the Yahara River and Lake Monona, and highlighted that “A goal of this community is to make lake and river improvements,” which includes “limiting or decreasing materials washed or discharged into the surface water.” Specifically, city efforts were being made to “decrease the quantity of nutrients (phosphorus and nitrogen) that contribute to the rapid eutrophication of the lakes in this area and 2) decrease or limit the introduction of heavy metals that may be detrimental to aquatic organisms and 3) decrease or limit the introduction of coliforms or other bacterial organisms that tend to adversely affect use of the waters for recreational purposes.”

Dyke attached a copy of Madison’s recently adopted ordinance and pointed to Section 5(c) covering effluent quality requirements. He highlighted that effluent quality requirements might be revised from time to time, so “discharges pursuant to initially prescribed requirements shall not create a vested right to continue such discharges and that permit holders must at all times meet revised effluent quality requirements.” Further, he noted, though discharges of grease and lard had been reduced due to company actions, water quality parameters such as phosphorus and coliform should be investigated more, and that dangers to fish and wildlife were unknown.[2]

He ended by asking if the issuance of a permit to Oscar Mayer “may not imply to the Oscar Mayer & Company that no further improvements in its wastewater quality will be necessary. It is hoped that this will not be the result of granted permits.” This concern notwithstanding, he then proposed that “the discharge should be allowed to continue during the improvement period, provided that no critical levels of materials are exceeded.”

National/Wisconsin Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits

The 1972 Water Pollution Control Act prompted the creation of National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits.[3] In 1974, Wisconsin also published Chapter NR 283, administrative rules that gave the DNR authority to administer the NPDES program through the Wisconsin Pollution Discharge Elimination System (WPDES). Two of the three goals outlined in NR 283 were the same as the interim goals of the Clean Water Act; the third was specific to Wisconsin: “It is also the policy of the state of Wisconsin that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited.”[vii] (italics added)

That year, water quality standards for Wisconsin rivers and lakes were approved by the EPA to complement other provisions of the new federal-state water pollution control program, which included limits for industrial and municipal waste discharges into navigable waters–for dissolved oxygen, bacteria, temperature, relative acidity, and “other characteristics in bodies of water classified as public water supplies, trout streams and recreational waters.” In addition, the standards required that “where possible, all Wisconsin waters be raised to a level of quality good enough for safe recreation and the propagation of fish and other wildlife.”[viii]

In addition to passing the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts in the early 1970s, Congress passed the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974 and the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) in 1976, which gave EPA authority to require reporting, record-keeping and testing requirements, and restrictions relating to chemical substances. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) was passed in 1976 and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA, commonly known as “Superfund”) in 1980. The goals of RCRA and CERCLA were to require responsible parties to investigate, clean up, and properly dispose of hazardous substances

Those who promoted the Toxic Substances Control Act. July 10, 1975.,,,

Legislation to prevent the proliferation of dangerous chemicals throughout the environment is “one of our most urgently needed environmental laws,” John R. Quarles, Deputy Administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency, said today. Testifying before the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Finance, which is currently considering legislation to control toxic substances, Quarles cited vinyl chloride as one chemical that should not have been allowed to enter the environment without proper testing for human health and environmental effects. Vinyl chloride, which is used extensively in the plastics industry, has been found to cause a rare form of liver cancer (angiosarcoma) in humans and has already caused the deaths of at least 15 Americans. In addition to vinyl chloride, Quarles cited fluorocarbons (Freons), bischloromethylether (BCME), polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs), and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) as chemicals now present in the environment that “point to the inadequacy of our present approach to controlling toxic substances.” “Existing Federal laws fail to deal evenly and comprehensively with toxic substances problems,” Quarles said.[ix]

“The Clean Air Act and the Federal Water Pollution Control Act,” Quarles said, “deal with toxic substances at the point at which they become emissions or effluents. Even the recently enacted Safe Drinking Water Act, while providing long-needed protection against contaminants in drinking water, deals with the problem at a point where the contaminants are very difficult to control.”

Only by requiring premarketing notification for all chemicals and testing for selected chemicals would EPA be able to assess adequately the risks that new chemicals pose to human health and the environment, Quarles said.

Oscar Mayer’s first WPDES permit application, city MGO permit application

EPA didn’t regulate storm water discharges under the Clean Water Act until the 1990s.

Greasy and fatty substances continued to be discharged from Oscar Mayer’s storm drains, contrary to the 1972 report findings that they had been mostly eliminated. In January 1974, the Director of Public Health Karl A. Mohr wrote to the mayor about an Oscar Mayer spill of “fatty like particulate matter” via storm sewer outlet into the Yahara River.[x] In a letter to the Director, the Oscar Mayer plant engineer manager explained that sludge-dewatering facility tanks were over-filled and “foamy materials floating on top of the liquid phase plugged the connecting line and eventually forced its way out of a manhole at the top…” “The cause of this incident,” he wrote, “was human error, or more specifically, a case of very poor judgment on the part of several people.”[xi]

About a month later Oscar Mayer applied for its first NPDES permit.[xii] As it was when the company applied for a permit under the Army Corps, the city was concerned that this would pre-empt its ability to regulate the company’s storm water discharge under its existing MGOs. On February 22, 1974, the Madison Public Health Director Mohr wrote to Carolyn Cates at EPA Region 5.[xiii] He attached a copy of the city’s MGO ordinance and noted that Oscar Mayer had recently applied for a permit under it.

The city reviewed the permit application. “Most of the non-storm waters being discharged are acceptable uncontaminated ‘non-contact cooling waters,’” Mohr wrote, “but cooling tower blowdown water “contributes approximately seven hundred pounds of phosphorus per year, as well as other chemicals, to our lakes.” He said the city was working with the company to decrease storm water runoff. “Will issuance of a permit by EPA hinder our efforts to obtain waste water quality improvements? We are not sure of the meaning of a three year permit for the company. If this means that the City of Madison would be restricted from requiring more stringent effluent standards, such as the exclusion of the cooling tower blowdown water from the storm sewerage system, we would be opposed to the granting of this permit.”

What about the plastics being discharged from Oscar Mayer’s storm drains?

On April 10, 1975, Bernard Saley wrote to Mohr and attached his January 1972 report, which included the observations about “bits and pieces” of plastics being discharged from the Oscar Mayer storm drains.[xiv] Saley had seen an article a couple days prior in the Capital Times–“Peril in a Package: Meat Wrapper’s Asthma,” and his memo advised Mohr to review the underlined sections of his report about plastics discharges. “Someone should be directed to determine if any of the waste products resulting from the manufacture of plastics at the firm are being discharged to the storm sewer and, if they are, whether any of these substances are included in the State (WPDES) or City (7.47 Ordinance) permits.”

The Capital Times article by journalist Whitney Gould that prompted Saley’s memo was about an Oscar Mayer worker who had serious, irreversible lung disease known as “meat wrappers’ asthma.” He attributed his disease to his work in the “slice-pack” area of the factory where machines produced plastic film and sealed it over packages of meat. Oscar Mayer, Gould reported, used millions of pounds of plastic powders per year, made of polyvinyl chloride and Saran.[xv],[4]According to a December 1976 report to the EPA, discussed below, Oscar Mayer’s waste water was segregated—some going to the sanitary sewers and some going to the storm sewers. “Clear water drainage from roofs and parking lots, water used for cooling plastic extruders, etc., is discharged to the city storm sewers,”it stated. [xvi],[5] This is the most likely source of the plastics Saley observed coming from the company’s storm drains.

Dane County Regional Planning Commission asks for money to help “sick lakes”—with focus on agriculture

According to the Wisconsin State Journal, in April 1978, representatives from the Dane County Regional Planning Commission (DCRCP) went to Chicago to nail down a large EPA grant to do a two year study on Madison’s ailing lakes. The focus, according to Bill Lane, the head of the DCRCP, would be “on weed and algae problems flouring in ‘the nutrient soup’ of area lakes.” The goal would be to “raise water quality to federal 1983 standards. That is, all waters in Dane County would be suitable for recreation in and on water and be suitable for fish and aquatic life and propagation,” Lane said. Though the focus would be on farm-related pollution, “[w]e want to end up with a plan to deal with every conceivable source of water pollution.” Even though Madison lakes may be the “most studied in the world,” Lane told the State Journal, “while we’ve defined the problem well enough, we haven’t been so successful with defining the solution…We have to do something just to maintain the present quality. Without any action, it will only get worse.”[xvii]

A few days later, the State Journal announced that the DCRCP got about $600,000 to find a “comprehensive solution to Madison area water quality problems.” The project was focused on rural and agriculture problems, not urban pollution sources.[xviii] Around the same time, the Army Corps of Engineers was proposing new regulations that would require farmers to get permits for agricultural operations, and they were not happy.[xix]

Oscar Mayer studied ways to reduce wastes–but ultimately concluded that it was too expensive

Given the significant environmental regulatory developments in the early 1970s, Oscar Mayer was under increasing pressure from local, state and federal regulators to reduce the amounts of pollutants it discharged to the sewage plant and into waterways.

In this context, two Oscar Mayer engineers and two University of Wisconsin engineers collaborated on a project to assess and reduce the pollutants in company’s wastewater, and in December 1976 they published a paper that they had presented at the “Proceedings of the Seventh National Symposium on Food Processing Wastes,” in Atlanta Georgia, sponsored by the U.S. EPA. At the conference, EPA informed food processing industries that they would need to “develop cost effective waste management systems” to comply with 1983 water quality requirements.[xx],[6]

Oscar Mayer’s 1976 proceedings paper described the processes at the factory at that time: “The Madison plant includes a modern meat processing plant, spice processing, and plastic film production areas as well as a hog kill rated at 1,000 head/hour and an 80 head/hour beef kill… Seventy-five percent of the water used is from the Company’s own wells. Wastewater at this plant is segregated. Clear water drainage from roofs and parking lots, water used for cooling plastic extruders, etc., is discharged to the city storm sewers. Sanitary sewage discharges directly to the Madison Sewerage System. Manure water (wastewater from the stockyards, stomach dumper, dehairing machine, and scald tank) is screened to remove the large solids, settled to remove grit, and pumped to an Oscar Mayer & Co. operated wastewater treatment site for biological treatment. The plant greasewater system collects the wastewater from all of the floor drains and processes throughout the entire plant. Greasewater is separately treated by settling and dissolved air flotation, and is then combined with the manure water for biological treatment (two stage trickling filter). The effluent from biological treatment is discharged to a Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District interceptor sewer. Sludge is dewatered by vacuum filter.” (italics added)

The “Oscar Mayer & Co. operated wastewater treatment site for biological treatment” referred to in the paper was the Burke sewage plant. In sum, “manure water,” “greasewater” and “wastewater from all of the floor drains and processes throughout the entire plant” went to the Burke treatment site, which sent its effluents to the Nine Springs plant. Overflow from the Burke plant also went to Starkweather Creek via a ditch—and presumably, as it had been for decades already, at least some waste sludge was still spread onto land around the plant, right next to Starkweather Creek.

The conference paper included tables outlining the large amounts of solids, total volatile solids, suspended solids, grease, nitrogen, and BOD (biological oxygen demand) discharged via the wastewater pipes to Burke and/or the Nine Springs treatment plant. Various adjustments were made to find ways to reduce the amounts of wastes produced, but given limitations of the old plant’s physical capacities, and amount of labor needed to change processes, the engineers concluded that it would be too expensive: “There is an argument that there is a need in the meat packing industry to conserve water and reduce pollutional loadings in wastewater…It is important that any changes which are made to reduce water use or pollutional loading be done without increasing human labor. At the present time, it is less expensive to pay the extra surcharge cost for over a ton of BOD rather than add one man day of labor to a process.”

Oscar Mayer was doing financially better than ever, but suddenly ended hog slaughter

Early in 1977, Oscar G. Mayer, the 62-year old grandson of the company’s founder, announced his retirement (though he would stay on the Oscar Mayer board).[xxi] At that time, Oscar Mayer reported the highest first quarter income in the company’s history, and the company’s CEO P. Goff Beach said it was due in part to an ample supply of hogs and substantial increase in sales of processed meats.[xxii]

Later that year, surprisingly, Oscar Mayer announced that it would end its hog slaughtering operations (dairy cow slaughtering would continue). State Agriculture Secretary Gary Rohde explained to the State Journal that the company made the decision because of “the declining supply of hogs in Wisconsin—in addition to the costs of new slaughtering facilities and environmental pollution.” He raised concerns about job losses (200 jobs would be cut) and effects on local hog farmers. A local farmer added that “he believed the Oscar Mayer decision also came because the plant was surrounded by the city and the company would continue to be plagued by odor and other problems.”[xxiii],[7]

In February 1978, a long State Journal article about planned changes at Oscar Mayer said in addition to shutting down the daily slaughter of 7,000 hogs, the company was looking for other places to site a new meat-packing plant and would further diversity into food-related manufacturing. Contradicting company statements in 1977, the new president said “It’s common in business to end things not going well and to add things that are productive”—and closing the hog slaughter operation would improve the company’s efficiency and productivity in other areas. Meat would be shipped by train and truck from the company’s Iowa and Illinois plants to Oscar Mayer to be made into meat products.[xxiv]

Challenges meeting new regulations, Oscar Mayer stops using Burke plant

The paper also reported that “[b]esides the decline in hog numbers, company officials cite the obsolete Madison slaughter plant and tougher pollution and odor-control standards as reasons for closing down the operation.” An article later that year, similarly, cited “increasing difficulty of coping with environmental, odor, and energy problems” as reasons.[xxv] “Phasing out the hog slaughtering operations,” the State Journal reported, “will reduce the amount of waste water sent to the company’s sewage treatment plant and decrease the odor problem in the area surrounding the plant.”

Though it’s unclear, evidence suggests that the DNR asked that the Burke plant be shut down around this time.[8],[xxvi] Presumably following from this request, the company stopped using the Burke plant in 1978, after which it performed secondary treatment at the site before sending wastes to the Nine Springs plant.[xxvii]

Oscar Mayer was facing other environmental challenges in addition to sewage disposal problems. It produced nearly all of its own energy onsite (burning coal and natural gas) and was facing increasing regulatory scrutiny about its air pollution levels. After Madison’s eastside was deemed in non-attainment for sulfur dioxide and particulates, DNR and the Dane County Regional Planning Commission began monitoring Oscar Mayer’s air emissions as part of a study to help meet federal air quality standards by 1983.[xxviii],[xxix] Oscar Mayer’s regional manager told the State Journal that the company would fight–“to the bitter end”– DNR’s charges that it was responsible for the non-attainment findings.

The End of an Era: General Foods purchases Oscar Mayer

In 1981, the Wisconsin State Journal announced that negotiations were pending to sell Oscar Mayer to General Foods Corporation of White Plains, New York for $464 million dollars—one of the largest (if not the largest) single acquisitions for General Foods since that corporation’s founding in 1920.[xxx] At that time, Oscar Mayer was the country’s third largest food company and its largest producer of lunch meats. It was the top private employer in the Madison area. The Madison plant had grown to nearly two million square feet in size and, the company claimed, was the largest single-site meat processing plant in the world.[xxxi]

The reasons for the sale were unclear—and apparently took many employees and investors by surprise. Some speculated that a worker strike in 1979 caused a rift in the Mayer family, while others thought maybe “the company had simply become too large for one family to manage.”

It’s not clear whether Oscar Mayer’s challenges dealing with sewage wastes and increasingly stringent environmental regulations influenced its decision to sell. Either way, local news about the sale didn’t mention the company’s environmental challenges. It was described as a “win-win” or “friendly acquisition.” Oscar Mayer’s vice president said “we feel no desire to sell the business…we are under no compulsion to sell. But General Foods is an excellent company. We feel they have a lot to offer us, and we think we have a lot to offer them.” A New York City brokerage firm analyst cited by the State Journal shared a slightly different take: “Oscar Mayer had run out of steam recently and their business had plateaued. What they needed was more money and marketing know-how, both of which General Foods can provide.”[xxxii] Oscar Mayer stocks zoomed upwards after the announcement of the sale, which was finalized a few months later.[xxxiii]

In 1983, the Oscar Mayer family, worth $200 million, was listed among the top 400 richest families in the country in the Forbes Magazine rankings.[xxxiv]

[1] MGO 7.46 was revised in 1998, and among other changes, the fines were increased to “not less than fifty dollars ($50) no more than two thousand dollars ($2000)” for each day of violation. MGO 7.47, “Regulations of Discharge of Non-Stormwater” was also revised in 1998 with further specifications about effluent quality requirements.

[2] He noted that the costs to send the storm water to the sewerage district (7.5% of its received daily flow) would be approximately $109,000 per year— implying that Oscar Mayer balked at spending this.

[3] There was plenty of pushback. 1971.2.12 CT–Nixon told polluters they’re off the hook; 1974.2.7 CT–EPA regulations called impossible; 1974.3.1 CT–Nixon threatened to cut off environmental funds

[4] A 2016 environmental site assessment document said, “A plastic extrusion line” on the ground floor of the processing building used “three types of resin (polyvinyl chloride, vinyl acetate, and a barrier resin) to create a three layered, food-grade plastic wrap that is used to package hot dogs.” (2016 Ramboll ESA)

[5] The Clean Water Act called for waste dischargers to install the “best practicable” treatment equipment of 1977, including secondary or two-state, treatment for community sewage and “best available” equipment by 1983, with the goal of “zero-discharge” of objectionable fluids by 1984. 1975.9.29 WSJ

[6] The Clean Water Act called for waste dischargers to install the “best practicable” treatment equipment of 1977, including secondary or two-state, treatment for community sewage and “best available” equipment by 1983, with the goal of “zero-discharge” of objectionable fluids by 1984. 1975.9.29 WSJ

[7] Oscar Mayer also had to find a new place to put its garbage because in 1977 the city’s Sycamore landfill, where it sent some of its trash, was “virtually overflowing” and couldn’t take any more garbage. A new county landfill was planned in Verona, but was facing some community opposition and a lawsuit so Oscar Mayer had to find an alternate site until that was resolved. 1977.1.21 WSJ

[8] An agenda item on a May 1977 Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District Commission agenda said, “An Oscar Mayer & Co. letter to the Wisconsin DNR in regard to the cessation of use of the Burke Plant and the construction of a secondary treatment plant on their lands was read.”

[i] Vig and Kraft, p. 12

[ii] 1972.1.20. MGO 7.47 (in lakes files)

[iii] 1975.6.4 WSJ

[iv] 1972.7.10 OM notice of application for a permit.

[v] 1972.7.31 City engineer to mayor about OM’s permit application.

[vi] 1972.8.14 Mayor Dyke to Dept of Army about OM’s application for a permit

[vii] Wis. Admin Code Chapter NR 283, 1974

[viii] 1974.5.15 WSJ

[ix] EPA press release – July 10, 1975, https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/aboutepa/quarles-testifies-need-toxic-substances-act.html

[x] 1974.1.7 Director of Public health to mayor

[xi] 1974.2.1 OM to public health explaining spill

[xii] 1974.2.12 OM’s first NPDES application

[xiii] 1974.2.22 City letter to EPA on OM’s permit application.

[xiv] 1975.4.10-Saley to city public health

[xv] 1975.4.8 –meat packers asthma.

[xvi] 1975.9.19 WSJ

[xvii] 1975.5.28 CT

[xviii] 1975.6.10. WSJ

[xix] 1975.6.27 WSJ

[xx] 1975.9.19 WSJ

[xxi] 1977.2.11 CT

[xxii] 1977.2.1 WSJ

[xxiii] 1977.11.18 WSJ

[xxiv] 1978.2.12 WSJ

[xxv] 1978.9.14 CT

[xxvi] 1977.5.10 WSJ

[xxvii] 1990.4.20 Consent order regarding the Truax Landfill

[xxviii] 1978.2.12 WSJ

[xxix][xxix] 1978.12.14 CT

[xxx] Winterhalter, 2019

[xxxi] Winterhalter, 2019

[xxxii] 1981.2.1 WSJ

[xxxiii] 1981.2.2 CT, 19981.5.6 WSJ

[xxxiv] 1983.9.29 CT