from Poisoning Paradise: An Environmental History of Madison

By Maria C. Powell, PhD

My Dad and his four siblings, growing up on West Wilson Street on the bluff overlooking Lake Monona, watched trash being pushed into the lake from the 1930s to the 1950s.

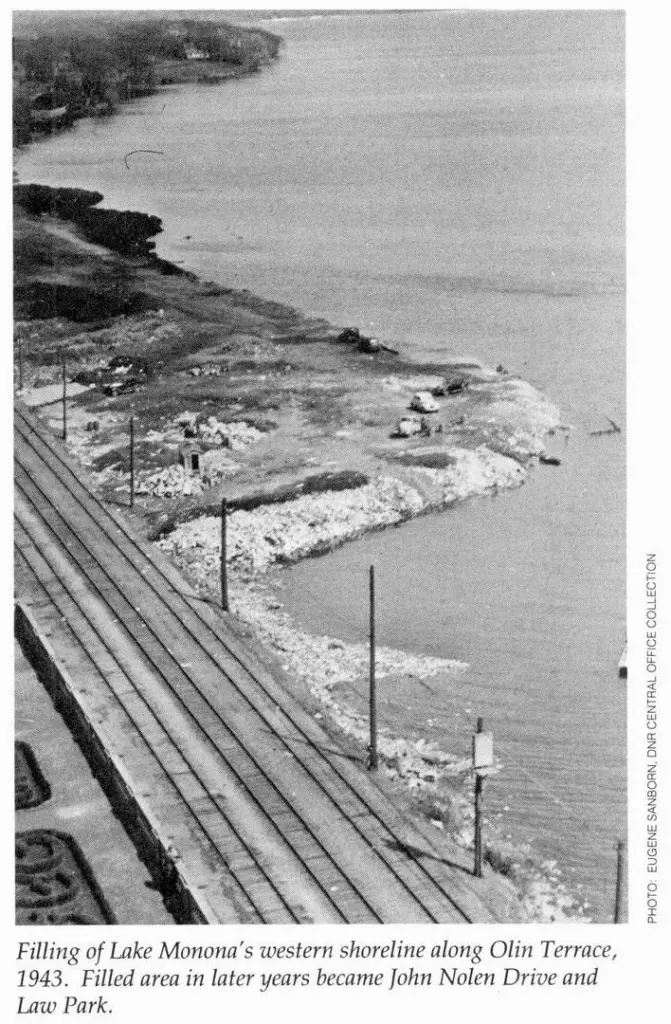

Madison residents had been dumping garbage along the north side of Lake Monona since the 1890s, if not earlier, but in the 1930s the city initiated a formal “refuse operation” to extend the downtown Monona lakeshore further out into the lake.[1] The city wanted to make more land along the shoreline to finally fulfill renowned city planner John Nolen’s 1911 “Model City” plan for Madison, which included Frank Lloyd Wright-designed civic center to connect the capitol area to the lake. It also needed a place to deposit increasing amounts of garbage, construction wastes, and other refuse as the city grew.

In 1989, in Recollections of a Former Madison Street Commissioner, James Brophy described how the city disposed of its growing amounts of wastes in the early 1900s, including filling many wetlands and bogs with it, and sending it to Dr. J. P. West’s piggery farms on the north side.

After this, he touted “another success story”—the “refuse operation” begun in the early 1930’s and ended in the 1950s that extended along Lake Monona from Blount Street to Broom Street.

“There is no place on earth for which God has done as much and man so little”

An earlier newspaper story described the reasons the city wanted to fill the lakeshore. In 1921, under the headline “The World’s Most Beautiful Capital City” city philanthropist, politician and deputy attorney general of Wisconsin Michael Olbrich wrote a long piece about how Madisonians had mucked up the stunning beauty of Lake Monona by allowing fishing shacks and railroad tracks on the shoreline instead of creating parks and beautiful architecture there.

Olbrich drew heavily from John Nolen’s past writings. Nolen’s statement, “There is no place on earth for which God has done as much and man so little,” Olbrich said, “still brands and sears us with the scorch of truth.” He added his own scathing indictment. “The history of city and state in relation to Lake Monona,” he wrote, “convicts us and those that have gone before us of a stupidity and a negligence that is nothing less than civic crime.”

He waxed poetically and at length about Monona’s stunning beauty, again citing Nolen. “Carved after the very ‘cunning’st pattern of excelling nature’ and ‘so lovely fair,’ Monona nestled within her bounds of hill and marsh and woodland. Providence surely was in a prodigal humor when she fashioned this miracle Monona. Here the poet might exclaim ‘was a site for a city which no other spot upon the continent could surpass.’”

But “the course of our development drifted from the poet’s dream,” he sadly lamented. “As if under compulsion of some monster of antique myth, across every thoroughfare leading from the city’s heart, we consented to or conspired in the construction of a great loom of death across whose frame of steel are shunted to and fro in constant oscification, the thunderous shuttles of destruction. Only upon the theory that death was a proper penalty for attempted use and enjoyment of the inalienable heritage of these waters, can we account for the construction of the railroad tracks that disgrace our water and humble our civic pride.”

The railroad tracks weren’t the worst offenses, in Olbrich’s view. “There was at least a certain element of dignity in the stark nakedness of this gross affront to common sense, this brutal trampling underfoot of the rightful aspiration of decent civic life.”

So the train tracks were “a gross affront to common sense” but were nevertheless “dignified,” according to Olbrich. But Madison decisionmakers added salt to the wound. “[A]s if our shame were not complete, that saving element of dignity was sacrificed by the addition of the addition of the grotesque horror of a squalid succession of shacks and shanties. Even with their partial abatement, as if the horrors of our conduct must still ‘on horror’s head accumulate’ the cusp of degradation already filled to the brim was set to overflowing and this priceless chalice of beauty and grace designed for love and adoration was transformed for entire seasons at a time into a cesspool of loathsome slime and stench—‘a cistern for foul toads to know and gender in.”

Monona’s beauty was “assassinated ‘in the very eye” by the fishing shacks, he continued. Her soul was “blinded, bedraggled, degraded” and she “like some sentient thing moans…against the indignity she has suffered at the hands of man.”

Olbrich scolded Madisonians for their abuse of Lake Monona: “A partial realization of the enormity of the offense should pale the pimpled rash of our civic conceit and stifle once for all the perennial hiccough of our self-satisfaction.”

So how can Madison reverse “the indignity” Lake Monona has “suffered at the hands of man”? Dump garbage onto her shoreline and build a highway there…

Under the heading “PUBLIC HEALTH—ONE BASIS OF IMMEDIATE ACTION” (caps in original), Olbrich argued that “The city has even less excuse for delay than the state” because conditions in Lake Monona had been deemed a “menace to the public health.” City health experts believed that deepening the lake by dredging would prevent weed growth, and the dredged sediments could be used to create a strip of “made land” outside of the existing shoreline. This “made land,” in turn, could be used for a park.

Olbrich was thrilled by these endorsements from city public health experts. “Our own good sense told us to do this all the while. Now that our opinion is buttressed with that of experts qualified to sit in judgment as to the requirements of public health, we may safely follow our natural instinct for the attainment of beauty to which we should have yielded long ago.”

Why were city wastes included in the plan for the “made land” on the lakeshore? “In addition to considerations of public health,” Olbrich explained, “the present city engineer suggests that the area for dumping the accumulated waste of our streets is so fast disappearing that in the near future the problem of a place of disposition in an economical and convenient manner is likely to grow acute. He suggests that the city should acquire the riparian rights outside the railroad tracks to make provision for a dumping ground.”

A highway was also part of the planned “beautification” of Lake Monona’s lakeshore. The city engineer’s predecessor, Olbrich wrote, “states that the time will come, and speedily, when provision must be made for a low grade or level highway across which our heavy traffic may be transported so as to avoid the hills within the city proper and relieve the congestion upon the present city streets. Such highway would find the natural place either just inside or outside the present railroad tracks and would not in any way interfere with the full development of the plan.”

Do Madisonians have the “burning will” to finally achieve John Nolen’s Model City plan?

“The burning will—the clear idea—the patience to organize—these are the unconquerable trinity which can create a new world out of chaos today, tomorrow, at any time,” Olbrich preached. He called on city leaders to create something on the lake front “better than anything of the kind that has so far been done in this country”—and he firmly believed that was possible.

“[W]hen we consider the situation and the size of the capitol, the character of the proposed group of buildings and the exquisite beauty of Lake Monona, it is not too much to say that this waterfront esplanade, a mile and a half in length, might equal any similar development anywhere in the world,” he opined.

“HAVE WE THE “BURNING WILL”? A heading asked (original in caps). “Is such a program feasible for the city? Surely so long as we have the ingenuity to tumble dirt down hill or haul muddy water out of the lake, the engineering phase of the task need not deter us. The sole question is do we possess ‘the burning will,’ have we the patience to organize?” Citing Nolen again, he argued that “we can and we will.” “No one can come intimately in contact with the citizenship of Madison without being impressed with its hearty, immediate and even generous response to demonstrated public need. “The high civic spirit” Nolen extolled is still here, Olbrich argued. “It needs but a little effort and a little energy to kindle it, until the social mass is alive all through with fires of high devotion.”

Olbrich was sure that Madisonians would be drawn to the lofty goal of making Madison “the most beautiful city in the entire world.” “Dull and sluggish indeed must be the imagination that does not quicken and thrill at the thought of our great ideal realized,” he waxed. “It is no cheap or common goal that has been set before us. This conception embodies nothing more nor less than making Madison the most beautiful city in the entire world. Generosity is challenged to vie with generosity for the attainment of this lofty end. Its glory is the glory of all and its benefits and inspiration would pass to our children and our children’s children, for a thousand, thousand years to come.”

James Law has “the burning will”—but first, the “squalid succession of shacks and shanties” must be removed

Local architect James Law, appointed Madison mayor in 1932, and re-elected for five terms, had the “burning will” Olbrich called for a decade earlier, and took the lakeshore land extension project on with zeal. It became his legacy.

But in order for this ambitious plan to go forward, in the early 1930s the city needed to remove the “grotesque horror of a squalid succession of shacks and shanties,” including some occupied by squatters. Street Commissioner Brophy personally participated in removing the “grotesque horror” of the fishing shacks, which commenced in 1934. In his 1989 memoir, he wrote: “The squatters were served notice to remove these structures by a certain date. Many ignored the city’s order and when I was assigned a crew of men to start dismounting the buildings, things really heated up. I was thrown into the lake two times the first day by angry boat owners. Thereafter, police were available to maintain order.”

Brophy’s first-hand account differs markedly from the May, 1934 Wisconsin State Journal story about the removal of the shacks, “City Begins Razing Boathouses on Monona at Owners’ Request,” which suggested that boat owners requested that their shacks be torn down, and some did so voluntarily. The mayor and city Building Commissioner “commended the spirit of the owners who volunteered to remove the structures.”[2]

In any case, voluntarily or not, eventually all the fishing shacks were removed. The city worked hard to gather enough trash, construction debris, dredged sediments, gravel—and whatever materials it could obtain–to create new “land” for what would become Law Park. Moving enough materials to the lakeshore took years, and a lot of labor—and New Deal funds came to the rescue.

As the city began pushing garbage into the lake, Brophy recalled, “the shoreline and lake bottom weeds and sediment held in suspension were a sight to see” and “we discovered very early in the operation that it would be necessary to find some way of controlling floating debris, since paper, cans, etc. would float into the lake.”

To deal with this problem, Brophy explained, the city purchased 40-50 foot-long “poles” (logs) from Washington state, drove them into the lake bottom with a pile driver mounted on a barge, and attached chicken wire to the poles to hold the trash in. The fence was visible three feet above the water. The trash was compacted with a tractor, covered with layers of soils excavated from city developments, dredged lake sediments, and coal ash from Madison Gas & Electric (MGE). The tractor operator “had to worry about sections of the fill breaking away and thus becoming a floating island,” he recalled.

What wastes were dumped on the lakeshore, and by whom?

The city began collecting residential garbage for the lakeshore in 1933, the year my dad was born, and city leaders also asked industries, businesses and citizens to contribute trash for the park. It was a community effort.

Henry Noll, a regular State Journal columnist, wrote on April 9, 1939— “Every bit of old paper deposited in uptown city waste boxes on street corners does its bit towards filling up Lake Monona shore which, when completed, will be park and named Law in honor of Mayor Law. All paper and refuse picked up in the center of the city from homes, business houses, and street waste boxes are dumped along the lake shore.” Presumably some of my dad’s family’s garbage was brought there.

Documents on the landfill—and well boring logs done decades after dumping ended– show that wastes dumped the on the lakeshore included a range of residential refuse, city construction debris, University of Wisconsin wastes, MGE coal ash, glass, paper, clothing, foundry sand, old newspapers, and a variety of other wastes. DNR documents and environmental investigations indicate that diesel fuel and other petroleum products were also likely dumped there.

What did the downtown Lake Monona shoreline look like?

In 1939, asphalt removed while rebuilding State Street was dumped at the shoreline, and in 1941, granite blocks were removed from the border of the rails circling capitol park and placed along the shoreline for the highway being constructed next to it (eventually called John Nolen Drive). The lakeshore must have looked horrific during the years garbage and debris was dumped there. In 1939, large photos of debris, barrels, and garbage appeared in the Capital Times under the caption “First View of City for Some Visitors.”[i] Sometimes trash fires broke out at the lakeshore. An April 1939 Capital Times piece reported that “plans to quench fires at the Lake Monona shore dump are being studied by Street Commissioner” who was considering asking the common council for funds to extend the city water service to the dump for putting out fires. The article also noted that “an attempt was made last year to have a fire department pumper at the dump but the solid matter sucked into the pump threatened to ruin the equipment.”[ii]

Mayor Law didn’t express any concerns about the shoreline being a garbage dump or about negative effects on the lake. When the city began collecting garbage to push into the lake to create Law Park, Mayor Law issued a statement emphasizing the importance of caring for the lakes. “I sometimes feel that many of us do not recognize what a tremendous asset our lakes are to the recreational life of our community and what an attraction they are to many visitors,” the Capital Times quoted him. “Our rivers and lakes commission has been rendering untold services in keeping our lakes clean.”[7]

Law bragged about the success of the city bio-chemist, Dr. B. P. Domogalla, in treating a variety of fungal, bacterial and parasite problems that had been occurring in the lakes during the 1930s, causing skin diseases in swimmers and infections in fish, with furfural and copper sulphate. Oddly, based on newspaper stories during this time, nobody connected these diseases or the bad water quality in the lake to the massive refuse operation going on at the shoreline.

Was this legal?

Dumping garbage directly into the lake, Brophy suggested, was perfectly honky dory to environmental regulators at the time. In fact, he assured, “[w]e were constantly being monitored by the State Department of Natural Resources. The monitoring was very easy for them since their office windows overlooked Lake Monona and with little or no effort they could review the state of affairs on a daily basis.” (The DNR was in the state office building built in the 1930s on West Wilson Street, on the bluff overlooking the lake.)

It’s not clear whether the U.S. Refuse Act (Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899)–one of the only environmental laws on the books at this time, and the oldest federal environmental law—applied to filling in a lakeshore with garbage. According to this Act, it is a misdemeanor to discharge “refuse matter of any kind into the navigable waters, or tributaries thereof, of the United States without a permit.” (See here and here. Actual text of the Act here.)[3],[4]

Whether or not the Refuse Act applied to this “refuse operation,” which the city called “making land,” there’s no evidence that the city had any kind of permit for it.

Who should pay for this grand Madison plan to “beautify” Lake Monona? What about the Public Trust Doctrine?

In earlier years, Nolen had proposed that the grand esplanade project depended on funding from the state. But Olbrich argued that Madison should share some of the financial burden. “To be truthful,” he asserted, “we must admit that the lion’s share of benefit and enjoyment to follow this development would come to the people of Madison.” He recognized, however, that this would be a “special obstacle to success,” because “[i]t is popular throughout the state to think of Madison as a sort of robber community, strategically located at the isthmus of Wisconsin life taking toll from the remainder of the commonwealth and giving nothing of solid worth in exchange…”

Given this, he argued, the state legislature probably wouldn’t approve funding for the project “until Madison demonstrates in a much higher degree than she yet has done the integrity of her civic purpose and the breadth of her civic vision.” It seemed “a natural division” to Olbrich that the state provide “the jewel and the setting” (the lake and the capitol) and Madison provide the needed shoreline. “Until we have done this let us cease to importune the legislature to open its cornucopia and shower benefaction on us. Let the city move then without further delay and take some decisive step in carrying out that portion of the Nolen plan which properly belongs to it.”

Olbrich’s 1921 promo for Nolen’s esplanade read like a primer for the city’s later legal argument to extend the city’s shoreline into the lake by “making land” in order to then build the esplanade and civic center over it. It’s not clear, but this plan seemed to violate the Public Trust Doctrine, a law created in the late 1800s which holds that all state navigable waterways are owned by the state and belong to the public.

So before going forward, the city had to convince the state legislature that these grand plans for the Lake Monona shoreline didn’t violate the Public Trust Doctrine—which in turn required convincing them that the endeavor would benefit the public.

In time, the city succeeded. In 1927, the legislature passed Ch. 485, which established a new dock line much further out into the lake from the original one, and 1931, the legislature passed a new section of Ch. 485 (ch. 301). Ch 301 read: “Said dock line on Lake Monona established by this chapter” authorizes the city of Madison to “construct and maintain on, in, or over said Lake Monona, but not beyond the established dock line, park, playgrounds, bathing beaches, municipal boathouses, piers, wharves, public buildings, highways, streets, pleasure drives, and boulevards.”

Perhaps to address concerns related to the Public Trust Doctrine, the bill was careful to clarify that the new dock line was not solely for Madison’s benefit, noting that “said dock line so established shall in nowise be construed as being for the benefit of riparian owners.”[5]

Chapter 301 presumably also gave Madison the legal authority to fill in the lakeshore with garbage. A May 15, 1931 Capital Times article, “New Dock Line Along Monona; Measure is Step in Improvement of City Shore,” reported that the bill “was introduced at the request of Madison authorities as a step for improvement of the city shore.” The new dock line was desired by the city because of “several important matters pertaining to the improvement of Lake Monona,” including the “proposed filling in of the lake shore from Bassett St. to the East side for construction of a lakeshore drive and enlargement of the park areas along the city shore of the lake.” The end goal of eventually creating the grand esplanade over the railroad tracks was clearly part of the city’s advocacy for the bill. “The improvement at the lake end of Monona Ave. is being constructed with a view of eventually building an approach to the proposed drive over the railway tracks,” the Capital Times said.[6]

Dumps burned and smoldered, residents protested, city biochemist squirted poisons

Anne Fleischli, a Madison lawyer and prominent citizen activist who opposed the construction of Monona Terrace at Law Park in the 1990s, wrote that layers of municipal and newspaper wastes, along with various industrial wastes, went to the Law Park landfill every day, and was “covered each day with a nice black layer of coal ash from another nearby neighbor, the electric utility”—Madison Gas and Electric (MGE). “By the 1950s,” Fleischli wrote, the dump was “1000 feet long, filled 260 feet out into the lake with a sharp six-foot drop-off at the edge of the water.”[iii],[7]

Newspaper stories revealed some citizen discontent about the dumps—and some recognition of their effects on lake quality. Noll’s 1939 column mentioned there were “several complaints” about “the present unsightly condition of the shore.”

In November 1939, Frank Weston, a long-time angler, lake advocate and former head of the Isaac Walton League, wrote a scathing letter to the editor to the Capital Times about the smoldering Madison garbage dumps. “The department of sanitary engineering at the capitol…can’t see the rotten pollution from these festering dumps” making its way to “poor old Lake Monona, where and because of which, the city-by-o-chemist will add a few more squirts of his poison to the poison-that-is, while his lakes and river commission basks on.”

Meanwhile, he observed, the chief of Madison’s fire department…lets his fire laddies spend whole days at a time, several times a year, pouring water into these subterranean, always smouldering fires…to the profit of the dumps, their landlords, and mortgage holding banks.” But “the fires are never extinguished; always they smoulder and greasy fumes ooze up into the otherwise clean air.” “It’s just plain damfoolishness to believe that, somewhere, amongst these powers-that-be, there is no power with the “intestinal fortitude” to abate this nasty nuisance…”

In 1940, protests by East Wilson Street residents convinced the city to halt dumping of paper and rubbish along the lakeshore until dirt from new building excavations could be secured “or a dredging program can be developed.” Residents objected particularly to dumping garbage at night.

Parking lots and highway eventually built on top of landfill

By the end of the ‘30s, the city began planning to build a parking lot over the eastern area of the shoreline, which had already been filled with refuse, because city and state workers had been demanding more parking near their work for years.[iv],[v]This took care of some of the disturbance and odor problems for nearby residents.

In 1938, Frank Lloyd Wright pleaded with the city to build his civic center on the lake, but it didn’t come to fruition then. At that point, the lake was still being filled in. In the early 1940s the city began considering a city auditorium at the park, and Frank Lloyd Wright proposed his first “dream plan” for it in 1941. It wasn’t till fifty years later (1990s), however, that Wright’s long-planned convention center was built on top of this lakeshore dump.[vi] By 1950, the shoreline was extended out 250-300 feet with wastes, and the proposed highway—later dubbed John Nolen Drive—was built by 1953.

Michael Olbrich didn’t live to see any of this. He died in 1929 of suicide, after an investment deal went bust.

[1] According to newspaper articles in the late 1800s, sewage from the state capitol, city and county government buildings, and jail discharged directly into the lake in the Law Park area until the city attempted its first sewage treatment plant on 1st street in the early 1900s; this plant failed and another one was built in Burke in 1914.

[2] Photo of fishing shacks from the Wisconsin Historical Society (Image 3647)

[3] The Act was originally used by the Army Corps of Engineers to keep waterways clear of refuse for navigation purposes.

[4] From Wikipedia: In 1948 Congress enacted the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (FWPCA) in 1948 to address water pollution problems, but this law gave the government limited enforcement authority. The Department of Interior, which administered the FWPCA (prior to 1972), developed a policy with the Department of Justice and the Army Corps of Engineers to use the Refuse Act as an enforcement tool, to complement the FWPCA. In the 1960s the federal government began to use it to control pollution, and in 1970 President Richard Nixon issued an Executive Order creating a new permit program under the Refuse Act. The focus of the new permit program was on industrial pollution. The Corps of Engineers began to issue the new discharge permits, but in 1971 a legal challenge halted the program. Congress enacted major amendments to the FWPCA in 1972. (See Clean Water Act.) Included in the legislation was a new discharge permit program, called the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES), which replaced the Refuse Act permit program. The amendments assigned lead responsibility for implementation of NPDES to the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Congress did not repeal the Refuse Act. The law is still used by the Corps of Engineers to prevent obstructions to navigation. In some pollution enforcement cases, the federal government has used it as a supplemental authority along with the FWPCA.

[5] In 1957, these two laws were used by the city’s attorneys in a Wisconsin Supreme court case, City of Madison vs the State, to successfully argue that the construction of the Frank Lloyd Wright civic center on Lake Monona did not violate the Public Trust Doctrine because the building was for the public and would benefit the public. These bills were again used to deflect concerns in the early 1990s about Public Trust Doctrine violations when Monona Terrace was finally constructed.

[6] The bill also gave the city authority to create Olbrich Park near Starkweather Creek; the article noted that the bill “will also give the city the right to fill in and straighten out the shoreline along Atwood ave., where the water is sheltered from the winds and therefore causes decay of algae. The city now owns a large amount of park land along the city shore of Monona which with the dock line will be improved.”

[7] In 1953, John Nolen Drive was built on it, and in the 1990s (completed in 1997) the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired Monona Terrace, purportedly held up by over 1700 steel pilings pounded through the landfill, was constructed between the highway and the lake.

[i] 1939.6.11 CT

[ii] 1939.4.7 CT

[iii] Fleishli’s article, p. 9

[iv] 1940.6.7 CT

[v] 1939.4.26 WSJ

[vi] 1941.6.4 WSJ