from Poisoning Paradise: An Environmental History of Madison

By Maria C. Powell, PhD

Burke still spewing sewage into Lake Monona; Oscar Mayer experiments

While the Yahara Lakes upstream-downstream battles raged on, behind the scenes the city was working with Oscar Mayer to solve the ongoing problems with the Burke treatment plant. The problems with the Burke plant were obvious as soon as Oscar Mayer began operating southeast of the plant in 1919. Throughout the 1920s, when citizens pointed to the plant repeatedly as a source of sewage to the lakes, government officials often deflected or denied it publicly—but internally they were aware that it was a pollution source to Lake Monona, even after the Nine Springs plant was built. According to city officials, the Burke plant, deeded to the sewerage district by the city in 1933, could not be shut down until the Nine Springs plant could be expanded adequately.

In May 1933, city engineer E.E. Parker told city officials that “grease and other waste matter” from Oscar Mayer “congeal upon entering the Burke plant, clogging screens and other equipment.”[i] In August 1933, a written “protest” from officers of the village of Maple Bluff was presented to the Madison Common Council, noting that the plant was operating over capacity and asking that the offensive odors be eliminated. A special sewage committee was appointed to meet with Oscar Mayer officials.[ii] A week later, after sewerage district commissioners and Maple Bluff officials conferred with Mayor Law about the situation, the city announced that “experiments to determine the best method for disposal of waste from Oscar Mayer” would be done. As always, each government entity attributed the most responsibility to another; even though the plant was technically their responsibility, sewage district commissioners called it a “city problem” because the city is responsible to collect the sewage within their limits.[iii],[1] In 1934, the city council approved the transfer of the Burke plant to MMSD.[iv]

Can Madison be a national leader in treating packing plant wastes?

Before the transfer, the city had agreed to help Oscar Mayer deal with its growing quantities of foul wastes. In the fall of 1933, the Mayor wrote letters to 38 packing plants and municipal engineers to find out how they handled animal processing wastes. Many said they discharged their wastes into the Mississippi and other rivers.[v] “Most cities seem to be gifted with a large fast flowing stream or large body of water which solves their sewage problems,” the Capital Times reported after Law’s survey was completed.[vi]

The city sewage disposal committee then recommended that $3000 be allotted to hire a Milwaukee bacteriologist to develop a method to treat Oscar Mayer’s waste—but some aldermen felt that the city’s biochemist Domogalla lead the study because it would cost less.[vii] The council approved $500 for a study lead by Domogalla, with an advisory committee of several university, state lab and Oscar Mayer scientists and engineers, and the superintendent of Nine Springs—with $500 from Oscar Mayer and the same amount from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF).[viii],[2]

The Capital Times said that Domogalla’s research, “if successful, will be of nationwide importance.” University authorities, however, warned the city and Oscar Mayer officials that to date no scientist had found a “satisfactory” methods of treating packing plant waste, even after studying the problem for years, and that many packing plants had spent “great sums of money” attempting, unsuccessfully, to dispose of their wastes without causing pollution, odor, and other problems.[ix]

Dr. Domogalla, champion of chemical fixes for the lake algae and stench problems—treating them with copper sulphate and other chemical compounds—decided to try a similar approach for Oscar Mayer’s sewage. In 1934 he told the Capital Times that his experiments aimed to find “a chemical which will reduce the packing plant waste to the same quality as domestic sewage so that it can be efficiently treated at the disposal plant.” The city finance committee approved $750 for these efforts and Oscar Mayer said it would contribute the same amount.[x]

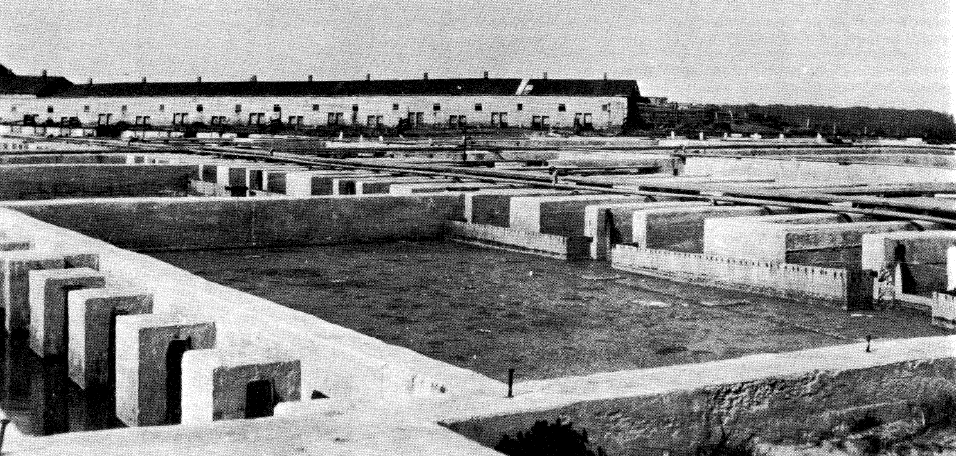

At this time, one of the city’s several “public health gardens” was at the Burke sewage site. They were called “sludge gardens” because they were fertilized with Burke sludge, which at this point primarily received wastes from Oscar Mayer. The “sludge garden” land was formerly used to grow food for animals at Vilas Park Zoo, but, according to the State Journal, “its fertility is now being utilized for the benefit of needy humans.”[xi],[3]

Domogalla says solution is near! City wants to patent chemicals used but won’t say what they are

At the end of 1934, the Capital Times reported, Domogalla announced that “the problem of disposing of industrial waste, thoroughly and economically, is about to be solved” and the experiments were nearly completed. Domogalla and his Oscar Mayer collaborators had tested 400 different types of combinations of chemicals. Chemical companies from all over the country were querying Domogalla, and even visited the Oscar Mayer plant, to find out the secret formula he had developed “to perfect the handling of plant waste on a large scale.”[xii]

In early 1935, before he was to share details of his chemical waste treatment formula to the city council, city officials expressed concern that because laws prohibit cities from patenting “formulas, discoveries, or inventions,” another entity would do so and the city and Oscar Mayer would have to pay royalties for the use of their own discovery.[xiii][4]A few months later, when he had deemed his experiments successful, Domogalla announced that he would in fact apply for a patent based on the city attorney’s advice. When presenting his findings to the city sewerage committee, Domogalla wouldn’t share what chemical or chemicals were used “pending granting of the patent,” but assured the committee that his experiments produced an effluent equivalent to that discharged now from the Nine Springs plant.

He also told them he was working with Oscar Mayer engineers “to determine was commercial use can be made of the solids extracted from packing plant waste,” and that Oscar Mayer planned to sell sludge as fertilizer. The city later approved $300 for a study of how the sewage could be used as fertilizer, with Oscar Mayer again contributing the same amount. The city and Oscar Mayer had begun drawing up plans for a sewage treatment plant at the Oscar Mayer site, designed by Domogalla.[xiv][xv]

Less than a week later, The Capital Times announced that “efforts to remove sewage effluents from Lakes Mendota and Monona will be victorious before the end of the year.” Adolph Bolz, vice president and manager of Oscar Mayer, said their preliminary treatment plant would be completed by the end of the year and would permit abandonment of the Burke plant. In addition to financially contributing to the cost of the treatment experiments, he said, Oscar Mayer had paid for the initial “experimental” treatment plant and “rearranging pipes in its plant to permit isolation of the concentrated waste matter.” Nine Springs plant superintendent John Mackin assured that chemicals used in treating the packing “would not be injurious” to the operations of the plant.[xvi],[5] At the end of 1935, the city issued a permit for Oscar Mayer to construct a plant onsite, which the company would spend $19,000 building, that would treat all the company’s waste before discharging it into city sewage mains and the Burke plant.[xvii]

In early 1936, the city approved more funds ($500) to complete “investigation of the sludge” and “official tests of the treatment plant.” The specific chemicals Domogalla patented for the treatments of Oscar Mayer wastes were not reported in any of the newspapers, but the author of the fishing column “Hook, Line, and Sinker,” Russ Pyre, wrote about Domogalla’s waste treatment experiments in his March 1936 column. Dr. Domogalla, he wrote “was surprised to find that certain chemicals introduced into the waste in treatment process tended to increase the oxygen content by two to three parts to every million gallons.” Domogalla also disclosed to Mr. Pyre that the experiments “may be the basis of further tests to determine the feasibility of using chemicals to release oxygen in stagnant lakes during the summer.”[6], [xviii],[7]

In November 1936, the “lakes investigation committee” of the Dane county board, which had sewage plant effluents analyzed by a lab in Milwaukee, reported that both the Burke and Nine Springs sewage plants’ effluents were contaminating the lakes with nitrogen-rich sewage with high bacterial levels. The report deemed the Burke effluent, in particular, as “putrid” due to disintegrated organic matter. The water where the Burke discharge went into Lake Monona was called “both unfit and unsafe for bathing” and the dissolved oxygen levels not sufficient for fish life. “The analysis of the Burke plant effluent,” the report said, “indicates that the raw sewage is not being properly and sufficiently treated” and “It is our opinion that a continuous flowing of this effluent into an inland lake would eventually impair its fitness for bathing or fishing.” The Nine Springs plant was declared “more efficiently operated” than the Burke plant.[xix],[8]

No more Burke effluent into Lake Monona? Well, maybe…

City officials told the Capital Times that as of December 1, 1936, the flow of sewage effluent from the Burke plant into Lake Monona had been stopped, and all Madison effluents were going to the Nine Springs plant for treatment. The Burke plant would remain in operation to handle Oscar Mayer’s growing amounts of wastes. Without use of the Burke plant, officials explained, the onsite Oscar Mayer treatment plant would be inadequate to handle all the company’s wastes. The plant was built with a capacity of 600 gallons per minute, but business had increased so much that 1,000 gallons per minute were leaving the plant during peak daytime periods.[9],[xx] Herbert O. Lord, chief engineer at the sewerage district, told the Wisconsin State Journal a slightly different story: “We are making an experiment by sending all sewage to the Nine Springs plant. It may not be necessary to turn any effluent back into Lake Monona in the future but we do not know positively at this time. In case adjustments or repairs are necessary, we may need to use the Burke plant again temporarily.”[xxi]

Variations in the news stories notwithstanding, clearly the Burke plant would not be abandoned, as citizens had demanded for at least two decades. For the time being, city officials assured that the plant’s effluent was purportedly no longer going into Lake Monona and the lake’s condition would be greatly improved.

Were Domogalla’s experiments really a success?

A 1937 memo by James Mackin, Superintendent of Operation at the Metropolitan Sewerage District revealed that Dr. Domogalla’s experiments in treating Oscar Mayer’s wastes were not as successful as he and the city told reporters. According to the memo, in fall 1936, when effluent from Oscar Mayer’s onsite treatment plant was sent to Nine Springs, it was not “up to the standard prescribed by the Commission”—there was “excessive grease, a high solid content and a high BOD” (biological oxygen demand) that were characteristic of raw sewage. Oscar Mayer effluents improved after MMSD began monitoring Oscar Mayer more closely but were still not up to district standards.

A big part of the problem, Mr. Mackin wrote, was that plant designers (which included Dr. Domogalla) ignored his questions about how sludge would be handled. So, when the one small sludge tank at the Oscar Mayer treatment plant quickly proved to be inadequate, the company discharged “a great volume of sludge into the marsh areas” around the Burke plant. To better handle this problem, the district allowed Oscar Mayer to store sludge in a series of tanks at the Burke site. These were also quickly filled so the district gave them permission to use more tanks there.[xxii] Mackin suggested that Oscar Mayer sewage effluents might be improved after better facilities were installed at Oscar Mayer and Burke for handling and disposing of sludge and “equalizing the flow of the strong fraction to the treatment works.” From 1937 to 1942, when the Department of Defense took over the Burke plant, Oscar Mayer stored large quantities of the plant’s sludge in various tanks at the Burke site while it wasn’t in operation.

Lake Monona problems don’t improve—more copper sulphate dumped on the problem

The elimination of the Burke sewage effluents into Lake Monona did not eliminate algae and odor problems in Lake Monona. In August of 1937, the common council again asked for more money for copper sulphate for treating the lake. The rivers and lakes commission reported that they had expected the closure of the Burke plant to result in the need for less chemicals, but “instead, a scum has formed on Lake Monona during this month which requires additional treatment.” If the council approved the request, a truckload of 50,000 tons of chemicals would be shipped to Madison as soon as possible; 60,000 tons had already been applied that year (fortunately, these units were mistakes—the amounts were pounds and not tons). Dr. Domogalla requested city funds for copper sulphate yearly after that; in 1938 he asked for enough funds to spray 80,000 pounds on the lake the following year.[xxiii]

In 1939, lake chemical treatments were delayed because the state conservation commission decided to require a permit each time the city sprayed the lake, due to concerns that copper sulphate killed fish.”[xxiv] Shoreline property owners, however, were more concerned about stench near their homes than about the fish. On June 1, 1939, livid about the odor problems, they demanded that the lake be “deodorized” with copper sulphate immediately. “Residents along the lakeshore are up in arms over the condition of the lake,” lakeshore property owner R.J. Nickles, former member of the rivers and lakes commission, reported to the State Journal. “The odors are almost unbearable.” Unless the treatments are done at once, he threatened “we will have to hold a mass meeting. We want relief.”[xxv]

The state permit would only take about six days to be issued, but Nickles argued that the algal growth would skyrocket within that time. With angry shoreline property owners planning a mass protest, the board of health voted unanimously that night to authorize Dr. Domogalla to proceed with treatments without the permit. Dr. Bowman announced to the Capital Times on June 2, 1939, that lake treatments had “started at the crack of dawn.”[10]

With the city fighting it tooth and nail, the state conservation commission backed off asking the city for a permit to spray chemicals. The county also voted to treat the lower lakes, under Domogalla’s direction, and city beaches were treated with a chemical called furforal “to prevent athlete’s foot.”[xxvi]

Dr. Domogalla “fights city’s scientific battles”

Madison was very proud of its leadership in treating lakes with chemicals, and Dr. Domogalla was viewed as a hero in this battle. An August 1941 Wisconsin State Journal article about the scientist, “Domogalla Fights City’s Scientific Battles,” gushed about his successes in cleaning up Lake Monona, noting that it was the largest lake in the world being entirely treated with copper sulphate and other chemicals. Domogalla, according to the article, “has taken up problems in sewage disposal, industrial odors and skin infections. All of them have been solved successfully.” Further the article, he wrote more than 20 articles for publication and in 1938 “achieved 11 lines of type in American Men of Science, the “Who’s Who” of scientific endeavor.” Under his leadership, the lab in the Board of Health building downtown was greatly expanded.[xxvii]

[1] Some council members at this time said that constructing a separate plant to treat Oscar Mayer wastes wouldn’t eliminate the odors near the plant because a large portion of the odor was from killing and dressing 2,400 hogs a day at the plant; the odors “rise into the air and are blown around by prevailing winds.” (1933.8.31)

[2] Two alders opposed using city money for this study, arguing that city taxpayers shouldn’t fund this–Oscar Mayer should pay for it.

[3] The former city incinerator was on the Burke site and was leased as an “oil reclaiming facility” that would take used oil from the city. 1935.6.29 WSJ

[4] On May 11, 1935, the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District sent a sent a letter to the Common Council ordering the city to construct a “preliminary treatment plant” at Oscar Mayer to reduce the plant’s packing waste before a new addition was completed at the Nine Springs plant. The letter was deferred to the city’s sewage disposal committee. 1935.5.11 CT.

[5] To date, the cost of the Oscar Mayer experiments had been $3253, with the city contributing $1250, Oscar Mayer $2410, and CWA $593 through the board of health. 1935.6.14 WSJ

[6] At that time, according to the column, the state board of health required that sewage effluents not decrease dissolved oxygen content of waters to less than two parts per million.

[7] 1937.3.6 MMSD letter suggests that chlorination was part of the treatment.

[8] The analyses found Lake Mendota water low in bacterial content and free of sewage contamination, indicating a “high degree of purity” and deemed it very suitable for bathing. Lake Waubesa water, it concluded had “a slight amount of sewage contamination” and though it was not safe for drinking, it was fine for swimming. Oxygen was sufficient for fish life. Kegonsa water showed no sewage contamination and no bacteria and was safe for swimming and health for fish life with sufficient dissolved oxygen.

[9] The company was considering building a large storage tank to store “excess sewage” that to “prevent the overloading of the company plant during the day.”

[10] The Dane County Park commission was also waiting for a state permit to spray lakes and had consulted the district attorney for an opinion on whether they needed one.

[i] 1933.5.7 CT

[ii] 1933.8.12. CT

[iii] 1933.8.20 CT

[iv] 1934.4.14 CT

[v] 1933.9.14, 1933.9.19 WSJ

[vi] 1933.10.11 CT

[vii] 1933.11.17 CT

[viii] 1933.11.22 WSJ

[ix] 1933.11.25 CT

[x] 1934.6.20 CT

[xi] 1934.6.24 WSJ

[xii] 1934.11.11 CT

[xiii] 1935.2.20 CT

[xiv] 1935.6.14 CT

[xv] 1935.5.23 WSJ

[xvi] 1935.5.29 CT

[xvii] 1935.12.13 WSJ

[xviii] 1936.3.1 WSJ

[xix] 1936.11.20 CT

[xx] 1936.12.21 CT

[xxi] 1936.12.22 WSJ

[xxii] 1937.3.16 MMSD letter

[xxiii] 1937.8.27 WSJ, 1937.9.21. WSJ, 1939.5.25

[xxiv] 1939.6.2 CT

[xxv] 1939.6.1 WSJ

[xxvi] 1939.6.5 WSJ

[xxvii] 1940.8.8. WSJ